Solar inverters

← Panel-Level Optimisation | The Good Solar Guide Contents | Batteries & Inverters →

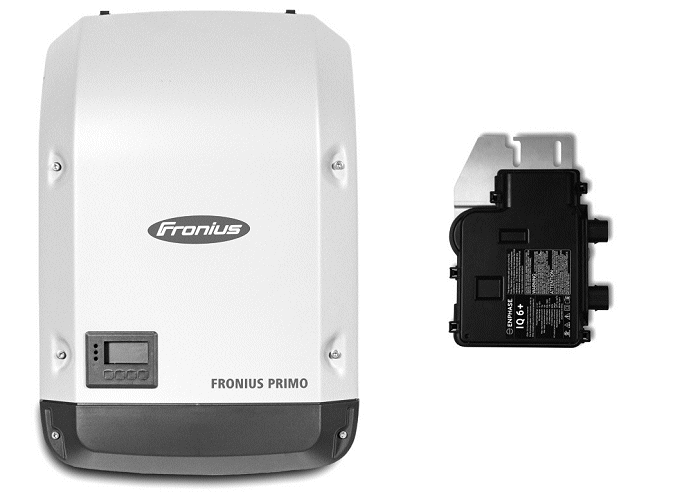

A solar inverter can be either a single central/stringl inverter (which is the size of a briefcase) or made up of multiple micro-inverters, the size of paperback books.

Figure 5.3 A central inverter (also called a string inverter) and a micro-inverter.

The job of the inverter is to safely convert the DC electricity produced by the solar panels into 230 V AC electricity, which is what everything in your home uses.

This means that all your solar energy will go through your inverter or micro-inverters. This is important for two reasons:

- The efficiency of your inverter directly affects how much energy you’ll get from your panels. A 2% difference in efficiency in the inverter means a 2% difference in your energy production. That means the efficiency of your inverter is usually much more important than the efficiency of your panels. In the next section, I talk about why, counterintuitively, less efficient solar panels give you the same amount of energy as more efficient solar panels. It sounds nuts, I know – but trust me on this.

- A central inverter works hard, gets hot and is the most common reason for solar power systems failing in the first few years of operation. Even the reputable budget brands have high mortality rates in the first three years. In fact, it was reported that Origin Energy recently took a $17 million hit to their business due to the cost of replacing an awful lot of Sharp inverters11.

Micro-inverters also work hard and are more likely than your panels to fail in the first ten years of operation. The good thing about micros is that if one fails, the rest of the system will keep working. If you have 20 panels, and one micro-inverter on one panel fails, the other 19 will hum along just fine, and you’ll only lose 5% of your generation until the defective micro-inverter gets replaced. If a central inverter fails, your entire system stops generating.

When shopping for a central or micro-inverter, efficiency and reliability are your two priorities. I would say that reliability trumps efficiency. After all, if you have to replace the central inverter, your solar system will be offline for a few weeks, you’ll lose an awful lot of energy and, if it’s out of warranty, it will cost you at least $1,200 to replace. Replacing a micro-inverter, including labour, is likely to cost $300 to $400.

Reliability is directly related to quality, so let’s start by looking at solar inverter quality.

Solar inverter quality

You won’t be surprised to learn that, in general, the more you pay for an inverter, the higher the quality and the more reliable it will be.

As an electrical engineer, I could spend the next 50 pages boring you senseless as I discuss how to design and build a reliable inverter that’s suited to hot Aussie conditions. I’d be happy to do this, but I’m guessing you wouldn’t be happy to read it.

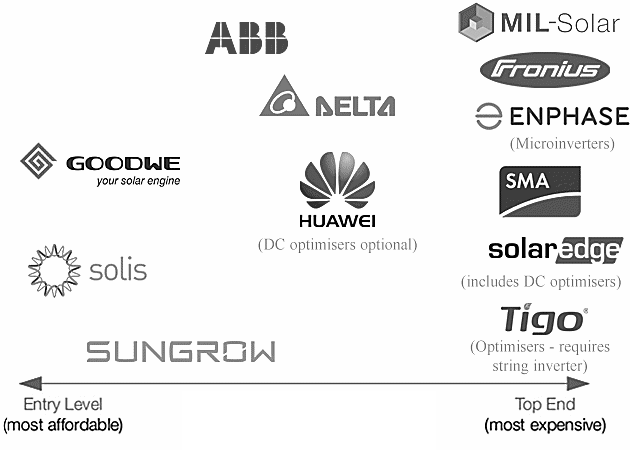

All you need to know about solar inverter quality in Australia is shown in this chart:

Figure 5.4 Reputable brands of inverter available in Australia.

Online resource: This chart will change as brands come and go – you can always find the latest version here: solarquotes.com.au/ichart

The inverter is the most likely component to fail in the first 10 to 15 years. This is because solar inverters work hard all day, and they do wear out.

That’s why, if you’re on a limited budget, I recommend prioritising a premium inverter over premium panels. The price difference between opting for a premium inverter (such as Fronius or SMA) versus a budget inverter is $700 to $1,000 per system.

Enphase (the only micro-inverter brand worth considering, in my opinion) is the most expensive of the lot, because as we learned earlier, you need one micro-inverter per panel.

What should I buy?

One way of looking at it is this: a budget solar inverter is about half the price of a premium one. That means you can replace a cooked budget one that’s out of warranty and be no worse off than if you’d bought a premium one. You will lose energy production while it’s being replaced, though, and the installer’s time will cost at least $200.

The other way to look at it is that a premium inverter is less likely to fail in the first 15 years. If it fails under warranty, the support and replacement should be fairly painless. Is that worth an extra $700 to $1,000? Only you can decide.

As you can probably tell, I’m a big proponent of buying quality and peace of mind if you can afford it. Like my granddad used to say: ‘Buy it well, buy it once.’ If the premium options are out of the question for you, I would strongly advise not going any cheaper than the brands on the left-hand side of the chart. There is some real junk out there.

Inverter warranties

The standard solar inverter warranty is 5 years. At the time of writing, SolarEdge offer a 12-year warranty and Fronius and Enphase offer a 10-year warranty; SMA will upgrade their warranty to 10 years for an extra $400.

If I were buying a solar power system right now – and I wanted a central inverter – I would buy SolarEdge or Fronius for the length of their warranty, or go with SMA with an upgraded 10-year warranty.

If I were to buy micro-inverters, I would go for Enphase – they come with a 10-year warranty.

Solar inverters for difficult roofs

You can skip this section if you have a simple roof!

If not, it’s worth knowing that a little bit of magic goes on inside an inverter, which you probably aren’t aware of. Despite what I said at the beginning of this section, the solar inverter has to do a lot more than convert the steady DC voltage into a jiggly AC voltage.

To get the most energy from a solar panel, you need to be careful about the electrical resistance that you connect to it. Too high and the current will stop; too low and the energy will be wasted.

It’s kind of like your garden hose. If you want to make the water go as far as possible, you can put your thumb over the end. If you cover the hose too much, you just get a big mist – but there’s a sweet spot, the ‘maximum power point’, where you leave a hole just the right size to get a powerful jet of water that shoots to the other side of the garden.

Solar inverters act like this. They vary their resistance until they get as much power as possible from all the panels they’re connected to. This maximum power point changes depending on how much light the panels are absorbing at any moment in time. That means it is adjusted every second. The device inside the inverter that does this is called a Maximum Power Point Tracker (MPPT).

Online resource: You can find the technical explanation here: solarquotes.com.au/mppt

I’m not just telling you this because I’m a geek and I think technology is amazing. It’s because I want you to know that you need to be really careful if your solar panels aren’t all pointing in the same direction. Panels that face different directions have differing amounts of sunlight hitting them so they have different maximum power points. That makes it impossible for a single MPPT to find the maximum of more than one set of panels at the same time if they are facing different directions.

If your home will need solar panels on multiple roof areas facing different directions, you may need a special type of inverter to ensure that you still get good system performance: a multi-string inverter (also called a multi-MPPT inverter), with one string or MPPT for each roof area.

Notice that I’ve used the word ‘may’, not ‘must’.

This is because there is one scenario where you can get away with one MPPT on multiple roof areas – when your roof area faces east and west and has the same number of panels on each side.

Any other configuration is likely to need more than one MPPT if you don’t want to cripple your system performance. A good installer will be able to look at your roof and work out how many MPPTs you need to maximise your energy yield.

Meanwhile, string inverters with more than two inputs are rare, so if you have a funky roof that points in more than two directions, you’ll need more than one central inverter, or you should consider PLO.

Solar inverters and panel capacity

A little known ‘secret’ of installing solar power in Australia is this: whatever size of inverter (in kW) you get, you should (wherever possible) get 33% more panels connected to it. For example, if you get a 3 kW solar inverter installed, you should get 4 kW of panels on the roof. I’ve already touched on this when discussing system sizing.

Because this isn’t common knowledge outside the solar industry, it is common in Australia for people to buy a solar system where the total capacity of panels in an array is the same as the capacity of the inverter. This has the advantage that you’ll almost never lose energy because the solar panels never produce more power than the inverter can use, but this isn’t much of an advantage.

Because panels rarely produce as much power as their rated capacity, it’s possible to add extra panels with very little energy being lost. This extra solar panel capacity can help the inverter to run at a higher average efficiency, which can almost entirely make up for what does get lost.

When the total capacity of the solar panels is greater than that of the inverter, the panels are usually said to be ‘oversized’ or the solar inverter ‘overclocked’. Because I think it makes a lot of sense, I tend to think of it as ‘right-sized’.

You can overclock your inverter by up to 33% and still get financial help in the form of STCs as part of the solar rebate. (If you go even 1 W over the 133% limit, your application for STCs can be refused.)

The beauty of oversizing your panels with the current rebate scheme is that the rebate is based on your array size, not your solar inverter size. The extra rebate usually covers the cost of buying the extra panels. The only added cost to you is the labour to bolt the panels to your roof – typically, $400 to $500 for $1,000 to $2,000 dollars’ worth of extra panels.

Oversizing your solar panels can be very cost-effective. Another real advantage lies in increasing your energy production when your local grid operator limits the inverter size you can install. For example, in many locations, people with single phase power are limited to installing inverters of 5 kW or less.

Online resource: How to oversize your solar panels if you choose micro-inverters: solarquotes.com.au/oversizemicro

11 https://reneweconomy.com.au/finally-a-push-to-crack-down-on-dodgy-solar-panel-and-inverters-44484/

← Panel-Level Optimisation | The Good Solar Guide Contents | Batteries & Inverters →

Questions or feedback about the content on this page? Contact me.