Image credit: NESCA

A growing number of Australians are trying to avoid the hellscape that is the current Australian housing market. The trend towards tiny houses shows it’s not hard to build a neat little dwelling and plonk it somewhere nice.

When it comes to powering said tiny houses, solar panels and battery storage can massively reduce bills down the track.

Read on while I weigh up your options for solar powering a tiny house or cabin.

On-Grid Small Homes?

If your structure doesn’t have wheels but does have plumbing, drains and electrical, then the fixed installation wiring rules of AS3000 apply, not the AS3001 standards for transportable structures. I’ve repaired some pretty wild examples of van-park dwellings running power from a pillar, via three buried extension cords — funnily enough, often that mess made it easier install proper consumer mains for grid-connected solar.

For a small home with access to a grid connection, an ordinary solar array or grid hybrid battery system — such as a Fronius or Sungrow — can be just the ticket. You’ll need a grid connection approval and a nice fat cable to the main switchboard to meet voltage drop rules, but it can be sub-metered if you need to divvy up the power bill.

Off-Grid Tiny Homes & Cabins

If your chosen site doesn’t have power available, then an off-grid solar power system is not hard to set up. Years ago you would have needed a specialist contractor and literally a ton of lead acid batteries, but there are some pretty nice packaged systems available now that don’t have to be hand-built on site.

That said, I would still recommend engaging an experienced solar qualified electrician because:

- Commissioning for off-grid solar isn’t something you want a novice doing;

- Qualified installation is required to maintain your warranty;

- If the lights go out, you might need someone to answer the phone; and

- Installers become your new power company (so local is preferred if possible).

Image credit Arkular.

Start By Sizing Up The Problem

Some 15 years ago, I found it fascinating to install off-grid Solar Depot systems for remote houses, simply because it opened my eyes to where the energy on the property is being used, and how to that influenced installation.

Generators were cheap, but noisy, while solar was quiet but expensive, and with more limited capacity. If you wanted air conditioning or a spa bath, generally you had to pour diesel on the problem.

Today, the technology has changed but the main considerations are largely the same.

The average job looked like this:

Step 1: Install a Solahart Hot Water Service (HWS) (close coupled, thermosiphon, tank on the roof).

Hot water typically represents 30% of total energy consumption, with cooking usually becoming the peak load for an hour or two a day.

Step 2: Plumb the HWS tank to a wood-fired range or combustion heater (the tank has to be gravity-fed).

This offers space heating and a boost to hot water during winter, and takes care of the major loads, along with a gas stove or BBQ.

Some customers would just opt for instantaneous gas-powered hot water and stove. This is a quick and dirty option, but bottle rental, as well as gas gets expensive — plus (as we all know) hell hath no fury like a partner who’s shower runs cold because you forgot to swap cylinders.

Step 3: Install a fridge.

This is the next largest load to deal with. We sold very efficient Vestfrost fridges (no longer available sadly). They came at an eye-watering $2,000, but could halve the size of the required battery bank, saving $10,000.

Step 4: Lights and appliances.

From here, lights and appliances are incidental. We would advise customers to wash clothes during the day and vacuum when it was sunny.

Step 5: Keep an ear out for the generator

All systems still required a fossil-fuelled generator (and still do today), which would auto-start at least once a month. Inevitably, however, the phone would ring at the end of March, because the summer sun had until then masked a generator failure.

If using things like a spa, clothes dryer or air compressor, then manually starting the generator first would save flogging the batteries.

For a more detailed explanation, spend the next hour or 13 with The Smart Energy Lab. DJ GlenMo will cover everything.

Do Not Buy A Cheap Hybrid

I’ve seen first hand the tears shed by installers and customers alike when they have simply chosen the wrong gear for the job. DIY forums are full of regretful folk who buy non-compliant crap online. Even those who should know better are out there installing equipment that isn’t fit for purpose. So be warned: if it seems cheap, that’s because it is cheap.

Transformerless hybrid inverters simply don’t have the surge capacity — the grunt — to start an inductive load like a fridge motor or rainwater pump. Tellingly, even if you buy a top-shelf Fronius Gen24, the warranty is void if it runs in off-grid mode more than 20% of the time.

Can Sungrow do it?

If you have a modest load, Sungrow hybrid inverters will work, with a generator, as a standalone power system with warranty support. Knowing how stable and reliable generators are1 I wish them luck with the endeavour.

Personally, I have never used a lightweight grid hybrid like that. Enphase did offer the option in the US and later withdrew support for it, and Tesla has also walked back on using the Powerwall 2 for off-grid applications.

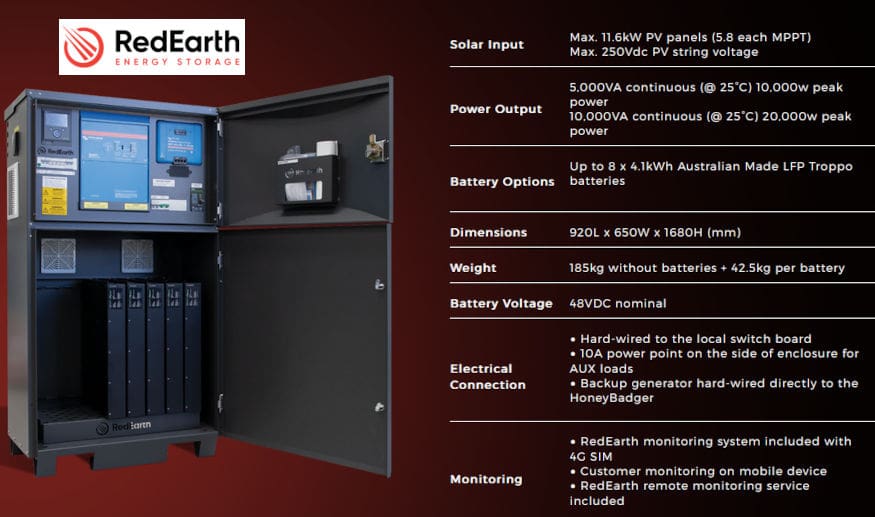

RedEarth DropBear has the same basic components that my house does. This is a really capable system you can have delivered almost anywhere by an all-terrain forklift, just like a pallet of bricks.

The Right Tool For The Job

The best solution for a proper grid-forming system is still Australian made. The Selectronic SpPro offers brilliant local support and a ten-year warranty, including for mobile installations. You can find these inverters integrated into pre-wired solutions, or hand built to power the Royal Flying Doctor Service out of Innamincka, and even running Sam Neill’s entire winery.

Victron produces another range of hardy products, with excellent monitoring and a vast array of accessories. Many installers use nothing else, but they are wise enough to know that five-year warranty support only comes from dealers, and actual technical support comes from a curious array of internet enthusiasts, on a forum loosely curated by Victron. There’s no actual phone number to ring.

RedEarth’s smaller offering has a little blue Victron heart

Just remember the ‘5000’ on the front of the blue Victron box is a part number for a 4000Va/3600W continuous rated machine. Provided you size everything to suit, Victron products can be great value.

Start With A Plan

When installing solar power systems for tiny houses and other little dwellings, the best advice I can offer is to get a solar installer involved early. Design the right roof and consider where the batteries are going.

The Solar Depot systems I mentioned above always worked best when we were involved at the outset. Power could be delivered from the shed as soon as it was built, and as the house went up, the plumbing was sized correctly, wiring was included and the roof was engineered for the loads.

But what actually makes the biggest difference is designing the building properly in the first place, so you don’t need as much electricity to power it. That means using passive solar design and plenty of insulation — and it’s not something you can tack on to a bog-stock kit home after it’s been delivered.

Footnotes

- We have a joke in off grid circles. When the off grid customers ring, it’s the generator at fault. The only customer who rings up with a non-generator complaint, is one with flat batteries, because they haven’t bought a generator yet ↩

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

If I read correctly my recently installed a battery with solar panels and the inverter will fail as the fridge freezer and rainwater tank pump that supplies all of our water requires too much current for the inverter to handle? We are 100% grid connected but use almost zero grid power if Im to believe the app that came with the Sungrow inverter.

There are possibly thousands of homes with a similar setup.

How big is your Sungrow Michael?

I would have thought COVID would have convinced most folk to avoid tiny houses like the plague. Tiny houses looks to be something 37m² or less, which means cabin fever and claustrophobia for anyone who doesn’t live outdoors, or who doesn’t only come home to sleep and shower – breakfast, lunch and dinner can all be bought, if not cheaply. For anyone who wants their own library, or who loves to cook, or has a family or … an overgrown shed won’t be fit for the purpose.

On the other hand a ‘tiny house’ or converted shed could be used as a service oriented business. It has space for customers, plenty of room for an office, and could even be split into separate business areas.

I have read of blogs about solar and recent advice from Anthony Bennett so it’s time to embarrass myself with a question that I have not seen asked before.

I read that heat affects the % out put of panels as well as inverters, to combat heat inverters can be placed in the shade in a garage or have shading outside.

I am aware that water and electricity are not a safe mix however when it rain panels get wet. My question pertains to the panels.

Q :- Is it not safe or viable to have roof mounted panels water misted when it get’s too hot the water running into the gutter and into a water tank to be reused. If this would work why isn’t a kit available? If it won’t work why not?

Hi Stephen,

Actually one of the advantages of floating solar farms is that evaporation makes them run cooler. There are also panels designed to have water plumbed across the back for water heating and solar electricity.

You could simply set up a sprinkler as they do for fire protection on houses in the bush, which would help clean panels as well but I would expect you’d have deposits of dissolved minerals build up over time.

Most panels would pick up around 0.35% extra power for every degree centigrade you can lower the temperature. My ready recking says on a 10kWp array that’s about 35watts. If the system can carry off 10 degrees of heat then you’ll have 350watts extra yield, which should be enough to cover running a pump?

Results might be better, I’ve hosed arrays and seen remarkable increases in yield until they dry, but I expect a permanent cooling system would present maintenance problems.

Good point Anthony.

The cost of pump and sprinkler and ongoing water loss through evaporation would be far greater than installing another 350watt solar panel,…which does not use any power,….but actually makes a larger system when it counts the most,… on cloudy days when heat is not really much of a consideration.

#itsalwaysthegenerator

There are off grid systems that don’t have generator problems, they’re the customers too tight to buy one. Occasionally they ring up to complain the batteries are flat.

Roof design: Room for 10 kW or more PV, northish facing, works for me, but half that again west facing, tilted up (mine’s 40 deg.) to grab the last of the sun is good for driving the aircon till sundown without battery drain on a 43 degC day. Thermal storage is cheap storage, and off-grid battery can’t be wasted on aircon. Even another 27 panels on my 14 deg tilted southern roof are a useful addition, according to PVwatts. I wish I’d hipped the eastern roof, to grab early sun as well, but the western late grab is worth much more in practice, I figure.

On a tinyhome, maybe provide ample blank wall space on the south for a sunshielded location for inverters, batteries, and MPPTs? Southern windows are thermally suspect anyway, and the gear must stay 60 cm away from both sides, losing 1.2m plus window width.

The “Heat & Cook” woodheater from Bunnings has an oven below, and removable cookplates for pots & pans. Its small footprint might suit a tinyhome. I bought an in-flue water heater, rather than add a fire-cooling boiler box in the stove. (Robs heat from the oven.) (May have to rejuvenate the old Ford ute for woodcarting, as the new EV doesn’t have the ground clearance for bush bashing.)

Hopefully battery prices will come down sufficiently that folk can before long adequately provision for off-grid without having to be technical enough to build their own. That currently seems the only way to add 40 to 60 kWh for sane money. An EV with LiFePO₄ batteries can better be kept close to 100% than more fragile Li-Ion, for a domestic power reserve if it has V2H.

My MG4 just has a little V2L cable, which could be taken to the domestic generator input, but can only provide enough power to keep a fridge and a freezer going, plus a light or two, so nothing flash. The low power output does make for longer duration backup, though.

If the tinyhome is portable, I’d make hinged solar verandas, lowered for transport. Grab more PV, and shade the walls to reduce aircon needs.

Yep, the standard off-grid cheat … solid fuel heating. Elephant in the very small room.

Transformerless inverters have come a long way, with Victron and others now producing double surge rating units, that are more efficient, are quiet (don’t have vibrating transformers) and warranted like their legacy gear.

Of course transformer units are still the most reliable for startup loads but don’t discount modern switchmode capacitor based inverters for household loads or in portable type applications.

Deye also makes some robust, great value modern Hybrid inverters that can live up to the task, CEC approved with long warranties.

Victron still have transformers in the Quattro and Multiplus-ii inverters.

It seems very old fashioned, but it still possible to put together your own small systems. I live by myself in a 40 sq m house (one size up from Tiny) and (of necessity) installed an off-grid system using the standard parts for caravans/camper vans and marine components. Apart from the 2kW (4kW peak) inverter, it is all 12V, so I installed it myself in the shed next to the house. The trickiest part was making sure that all the cabling was of sufficient size to avoid overheating.

It has 500W solar panels through a 50A inverter into 300Ah lithium batteries. It runs all the LED lights/fridge/washing machine and workshop tools very reliably, and even an electric motorbike. And there is a 2kW portable generator which gets used about once a year in midwinter. The average power use is about 1kWh per day, and the power bill spread over 10 years will be about $400 per year. I tend to save big power demands for sunny days when over 3kWh is available.

Of course it is too small to run bigger things like hot water, stove or house heating; I ended up using gas cylinders for the first two, and a pellet fire for the latter, as they were more economical than the alternatives, about the same cost per year.

In the long run I hope to get an EV, and then I will install a big system on the roof shed, and everything else electrical. But at the moment, it is the right amount of power for my needs.

Have you not considered a home made solar hot water system… using black piping on the roof to a solar / water tank collector?

I presume there is no A/C but do you run fans or have you a good ventilation system for cooling?

While this blog is about all thing electrical are you on acreage and are you attempting to be self sufficient with food and other things or it just with power?

Ah yes, the hot water problem. It is the biggest power demand. I looked at solar hot water heaters, but unfortunately every legal system demands a guaranteed minimum temperature and that means backup by electricity or gas. And that doubles the price. So I just used the gas. The other complication is that I live in a cold part of Tassie and there is a lack of sun in winter.

But eventually I’ll get a heat pump run from more PV. Cooling is a rare requirement down here!

And I do have a large garden from growing my own provisions.

Ah Tasmanian; say no more – cooling not required as you say.

The Victron 5000 you spoke of actually stands for 5000vA or 5kVa and 4kW rating at 25°C. Victron do derate a fair bit the hotter they run but proper system design can mitigate this fairly easily. You can also get 10-year warranty on Victron inverters, just get the installer to enquire with their supplier.

Although Victron don’t do support they do support their suppliers, but its the suppliers responsibility to provide that help to the installers; it does get a bit convoluted, but once the system is installed and commissioned correctly there shouldn’t be any issues, well at least in my experience. The supplier should be able to provide tech help and training and if they are unable to, save yourself the heartache and find a supplier that will. There are plenty of Victron suppliers.

Electric hot water can easily be used in an off grid home however, and a big however, it does greatly depend on the size of the array and the customer needs to be aware that if they have a week of rain they will need to run their generator. CatchPower Catch Control (formerly Smart Solar Relay) can be triggered by frequency, which is perfect in a Victron or SMA system that use freq shift to curtail solar inverters. This might work out well for the customer, and cheaper than gas, but this is where a good or bad design and make or break a system, and peoples hearts.