And you thought the election was a shock result…

I have good news. PVEL — a standards testing company — has released a solar inverter scorecard. It describes how a dozen different tests were performed on a variety of inverters and which were the top performers

The bad news is the inverter scorecard is focused on North America and none of the top performing inverter models are available in Australia. Even if you got your hands on one you wouldn’t be able to use it here, as North American current is different because electrons spin counter-clockwise in the northern hemisphere.1 Also, some of the inverters that did well are too large for normal residential use.

Another problem with the scorecard is it only shows which solar inverters were top performers and not which did badly or whether or not an inverter that wasn’t a top performer was even given a particular test.

Despite these drawbacks I’ll describe the tests performed and which inverters did well. After all, if a company produces solar inverters that perform well in North America they are likely to make ones that work well Down Under. The brands that received the most top performer ratings were Delta and Huawei and they are both available here.

Who The Hell Is PVEL?

PVEL stands for PV Evolution Labs. It’s probably not evolution like this:

Because that’s just a cartoon. It’s not even biological evolution like this:

Which is scary if you happen to know it shows bacteria evolving resistance to increasing concentrations of antibiotics.

Instead it’s about the evolution of solar technology thanks to human-guided change.

PVEL tests solar panels, inverters, and other solar power hardware to find out what works well, what doesn’t work well, and what meets standards. It was part of DVNGL, which is a huge Norwegian standards organization. I wrote about their solar panel scorecards in 2016, 2017, and 2018. But now PVEL has been spun off and made an independent solar testing organization. This could be because DVNGL is heavily involved in the oil and gas industry and they wanted to avoid a potential conflict of interest between those working to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and those who want to watch the world burn.2

Issues With Inverters

Inverters are the most likely to fail part of solar power systems. This is because:

- They perform many functions and so are complex.

- They contain hundreds of different components and if one fails often the whole thing does.

- They are dependent on software that can be faulty and software updates can introduce new problems.

Just like me.

Testing Methodology

PVEL tested 35 inverters from 12 different manufacturers. While manufacturers pay to have their products tested, PVEL selects the solar inverters used for testing to make sure they are representative of what the company sells and not specially made high quality versions.

What we’re not told is which inverters were tested and which did poorly. All the scorecard does is tell us which were the top performers in a test. If you want details on what are the dregs of the inverters they investigated you’ll have to pay PVEL for a full report and then keep it confidential and not blab about it online.3

Passive Chamber Testing

The first set of 3 tests is called Passive Chamber Testing. The inverters are shoved in a chamber and exposed to extremes of heat, cold, and humidity. It’s called passive because the inverters aren’t turned on. The goal is to test how physically tough they are and whether or not they are likely to withstand years of exposure to the weather.

The 3 tests in this section were:

- Damp Heat: Temperature is held at 85 degrees and humidity at 85%

- Thermal Cycling: Temperature is cycled between -40 and 85 degrees

- Humidity Freeze: Cycled between 85 degrees and 85% humidity and -40 degrees

We’re not told how long these tests last for or how many cycles they were run for but they do say it, “…builds and expands on the PV module IEC 61215 test standard.” To meet that standard the tests would need to be run for a minimum of:

- Damp Heat: 85 degrees and 85% humidity for 1,000 hours (42 days)

- Thermal Cycling: 200 cycles between -40 and 85 degrees

- Humidity Freeze: 10 cycles between 85 degrees and 85% humidity and -40 degrees

This is much less than what PVEL put solar panels through, but panels are expected to — hopefully — last at least 25 years, while the many solar inverters are doing well if they last more than 10 years. The minimum product warranty for solar panels is 10 years while the majority of inverters only have a 5 year warranty. Given the current expected life expectancy of solar inverters it is reasonable for PVEL to be less harsh than when testing panels.

The two solar inverters that weathered these tests the best were the 8 kilowatt Delta M8-TL-US and the 7.7 kilowatt SMA SB7.7-ISP-US-40:

While these are both US models that aren’t sold here it still indicates Delta and SMA know how to make durable inverters.

While we’re told these two solar inverters came out smelling of roses, we’re not told which ones came out smelling of ozone generated by sparks and short circuits resulting from sub-optimal construction. But we are given the following graph:

While all survived thermal cycling without having their performance seriously affected, not all came out of the Damp Heat and Humidity Freeze tests alive or unscathed. A significant number either failed to work or had their performance degraded.

Thermal Performance Test

While the previous tests were passive and run with the solar inverters turned off until tested, the Thermal Performance Tests use switched on inverters and consisted of the following:

- Powered Thermal Cycling: The inverter is operated while the air temperature is cycled between the manufacturer’s stated minimum and maximum operating temperatures.

- High Temperature Operation: The temperature is cranked up to the inverter’s maximum operating temperature and left there while it is fed current that simulates being connected to solar panels.

- Low Temperature Operation: The inverter is cooled to its minimum operating temperature and then operated while the air is kept at that temperature.

These tests are done with multiple temperature sensors inside the inverter. If these find some electronic components get much hotter than others it indicates those components are likely to fail early. If the solar inverter derates and starts doing less work to prevent heat levels getting high earlier than the manufacturer says, it indicates the inverter might last but it will provide less less energy on hot days. PVEL describes this problem using bigger words than I did:

The best performers in these tests are shown in the graphic below:

While the Delta, SMA, and Huawei inverters could all potentially be used residentially, the Schneider Conext CL-60A inverter is 63.4 kilowatts, which is far too large for any normal residential use. At 24 kilowatts the Fronius Symo 24.0-3 could theoretically be used as a residential solar inverter4, but a bloody big roof that could support 200 or more panels would be required.

Performance Testing — Efficiency

How much energy an inverter supplies depends on its efficiency at turning DC power from solar panels into the AC power homes and grids use. Three tests are used to measure this:

- MPPT Efficiency: This tests how well an inverter’s Multiple Power Point Trackers (MPPT) can adjust to fluctuations in output from solar panels.

- Conversion Efficiency: This measures how efficient a solar inverter is at different power levels and averages the result.

- Energy Harvest: This test involves measuring how well an inverter performs through a simulated day including morning startup, full day operation, and evening shutdown.

Top performers in these tests were:

All the Huawei inverters listed above as top performers are too large for normal household use.

Operational Envelope Testing

Despite the name, Operation Envelope Testing is nothing to do with working out what the best envelopes for operating on people are.5 It instead consists of three different tests:

- AC Operational Envelope: This tests if the inverter operates at full power while the grid AC voltage is fluctuated between the limits the manufacturer allows.

- DC Operation Envelope: This is similar to the AC Operation Envelope test except voltages are fluctuated on the DC power that would come from solar panels.

- Transient Response: This measures how well the solar inverter responds to changes in grid voltage and frequency.

If, during these tests, an inverter derates and reduces output earlier than it should, or trips and stops operation altogether earlier than it should, then its total potential energy production will be reduced. The top performers on theses tests were:

Field Testing

Field testing involves putting the inverters in a field and connecting them to solar panels to see how well they perform under real life conditions. Two tests were performed:

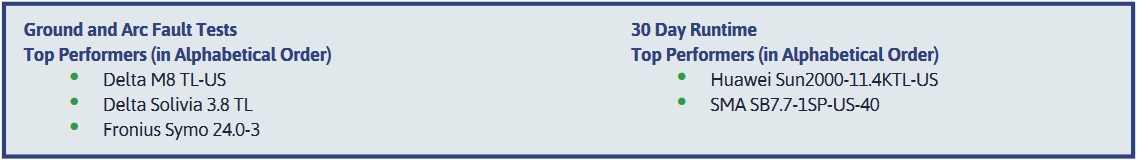

- Ground and Arc Fault Tests: Lightning is an example of an electrical arc. While arcs in solar systems won’t be that powerful, they are still dangerous and this test measures how well inverters detect arcs and shut the system down before damage is done.

- 30 Day Runtime: The inverter is connected to solar panels and allowed to operate for 30 days. They are graded on downtime, faults, and performance.

Top performers in field testing were:

Brands That Look Best Overall

Of the 12 brands of solar inverters tested only 5 managed to show up in the top performer results. If I put those brands into a chart and show which tests one of their inverters got top performer status in, it looks like this:

This makes Delta look like the top brand overall, but we can’t conclude that because we don’t know if inverters were submitted for testing where they weren’t rated as a top performer. Also, some tests are more important than others. For example, I’d rather have a solar inverter that is durable and lasts over 10 years but with only mediocre efficiency than a highly efficient one that stops working after 6 years.

But while we can’t draw any firm conclusions, being rated as a top performer does mean the manufacturer knows how to make solar inverters that perform well in that area and this does make Delta look good. Huawei also comes off looking very good. Schneider is next, although that is not a common brand in Australia, while Fronius and SMA are both well regarded brands here.

It is likely that PVEL will produce an inverter scorecard every year and hopefully future ones will feature versions of solar inverters sold in Australia.

Footnotes

- Currently the clockwise spinning electrons in the windmills of my mind are producing a surplus of bullshititrons. ↩

- As DVNGL is a Norwegian company I presume the solar staff and the oil and gas staff were constantly attacking each other with their Viking longboats. ↩

- Even then I don’t know how much information they will reveal. ↩

- if the DC voltage was kept under 600V ↩

- Everyone knows the scalpel envelope wins hands down. ↩

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

Was solaredge part of that testing?

Wow.

Informative, a great read, and a few laughs thrown in.

Very unlike other reports. As a solar installer, I look forward to reading more of your exploits.

Does the rate of ‘ electron spinning’ vary depending on the distance from the North Magnetic Pole or the equator ???

This information could be crucial when the magnetic polarity of the world inverts soon as predicted by the doomsayers.

As a solar installer in Canada, I am very curious on a comparison between Huawei and SolarEdge as temperature changes can be drastically high at 40 Degrees Celsius to drastically low at -40 Degrees Celsius. Huawei wasn’t listed in the chamber test which makes me curious if it can really handle our climate. Anyone have any experience with Huawei?

Two questions from me:

1) Temperature: degrees – Fahrenheit or Celsius?

2) If these are ‘commercial’ inverters tested, can we really extrapolate results to the ‘residential’ ones available in Australia?

The temperature is Celsius. Some inverters were residential sized and getting “Top Performer” results for commercial sized inverters indicates the manufacturers know how to make a good inverter, so it is evidence that their smaller inverters will also be good.

I believe there is no reason what so ever, to assume that a manufacturer knows how to make a good commercial inverter should automatically make a good residential one. Manufacturers especially Chinese ones, constantly make new models less expensive to produce, Tests results are out of date when they are published, because new models are already launched and the old ones that were tested are no longer produced. A commercial inverter is produced over a longer period of time than residential inverters.

Temperature testing have to also be tested cold start at max and at min operating temperature. It is essential that an invewrter will start at -40 in the morning if specified to do thet.

In my opinion this test as presented is useless, and I would never ever pay a cent for the full report.

It seems the report they put out was not great with very little ‘detail’, openness, clarity, planning or willingness to share the results which I find myself asking why release a report that leaves more questions than answers? Are they selling the data or has some vendors managed to alter or highlight strengths more so perhaps?

Overall not a big fan of the report but appreciated you taking the time to share and write up about it and do your best to try ‘decode’ the results.

I do think they should have separated perhaps large, medium and small inverters into separate categories as to me it seems unwise to compare a 65Kwh inverter with say a 20Kwh inverter?

Not listing results in ‘order’ also seemed a little odd but rather than listed only the top 1-3 alphabetically, again seems odd to me and can’t get my head around this…

My conclusion is well that was a waste of a report and time… I did not learn much and only kept reading due to the humour included in the article by SQ team

Top of the tree rating is a bit irrelevant if they cost $15000 ,obviously they don’t but it would be more pertinent if the capacity and cost was included.