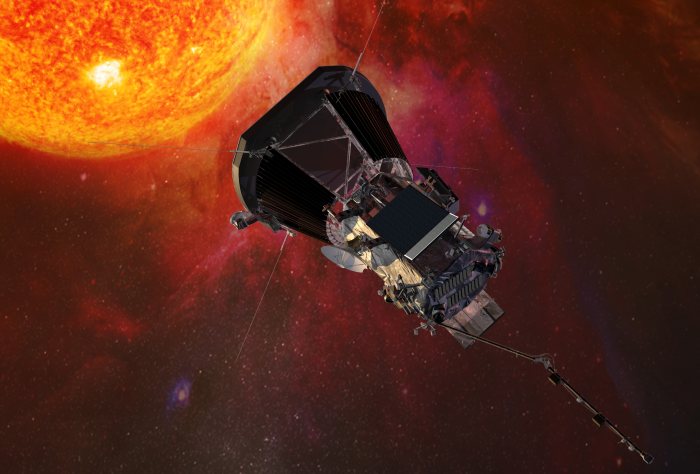

Parker Solar Probe | Image: NASA

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe spacecraft will fly closer to the Sun than any other mission – and its solar panels will require special protection to survive temperatures reaching around 1,370C.

The panels will be protected for the most part through the use of an innovative thermal protection system (TPS) consisting of a 2.4 metre shield. However, when the probe is closest to the sun, a small part of the array will be exposed past the shield so enough power for the spacecraft’s systems can be generated.

To provide protection, a unique cooling system has been developed consisting of an accumulator tank, two-speed pumps, plus four radiators made of titanium tubes and super-thin aluminum fins just 0.508 millimetres thick.

Surprisingly, the liquid to be used in the cooling system isn’t a complex concoction – just 5 litres of de-ionised and pressurised water. NASA says this is because few liquids can handle the temperature ranges the cooling system will subjected to like water.

The solar cells themselves, while having standard glass (or what counts for standard in space applications), have a unique ceramic carrier soldered to the underside attached to the platen (panel substrate) with a thermally conductive glue; enabling conduction into the cooling system.

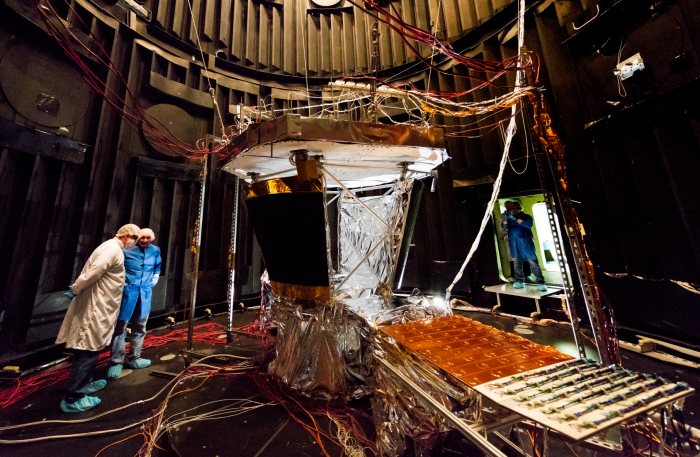

Parker Solar Probe PV Array Cooling System

Even with all this protection, the solar panels will still be on the warm side – up to 160C.

Another challenge of the mission is that as the probe will be so far away, human intervention won’t be possible and the TPS’s operations will need be handled autonomously by Parker Solar Probe’s onboard guidance and control systems.

Launching in 2018, Parker Solar Probe will get within around 6.4 million kilometres of the sun’s surface. The mission will provide new data on solar activity and improve the ability to forecast major space-weather events.

Space weather can have a huge impact on Earth, both to satellite operations and terrestrial activities. The solar storm of 1859 caused havoc and if such an event occurred today, the impacts could be far worse – for example, power could be knocked out on the USA’s eastern seaboard for a year.

You can stay up to date with the Park Solar Probe mission here and learn more about the cooling system here.

While nothing like the extremes the Parker Solar Probe’s solar array will face, heat also presents a challenge to solar panels here on Earth as the output of most starts to drop off once the temperature of a module exceeds around 25°C.

Not all panels are equal in this regard and performance past 25°C will vary depending on the module’s temperature coefficient; a number that describes how well solar panels can handle hot temperatures. It’s one of the issues to be aware of when comparing solar panels.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

Speak Your Mind