Now you know what the those DNV-GL engineers *really* get up to in their secret European HQ…

DNV-GL’s PV Module Reliability Scorecard Report for 2017 is out1 and gives some fascinating results. You can follow that long link in the previous sentence to download your own copy of the report, but for your benefit, I’ve included my own unique analysis below, where I will give my interpretation of the results in 2,000 words or less.

Or possibly more. I’ve only just started writing so don’t really know just how many words I’ll require, but if it looks like I’ll go over my self-imposed limit I can just leaveoutsomespaces, so it’s not really a problem.

The DNV-GL Reporting Process

I wrote about DNV-GL’s Module Reliability Scorecard for 2016 and described their reporting process, which is similar this time around. But there’s no need to skip back to my old article. I’m quite happy to go over it again. This is because I am conscientious and want to provide you with all the information you need and definitely not because I get paid by the word.

You can rest assured there is absolutely no way I would ever just go on and on, adding more and more words for no worthwhile benefit, boon, advantage, or gain, just to pad, prolong, expand, extend, or even elongate a piece of writing. Besides, I have my self imposed 2,000 word limit, so I certainly don’t have the luxury of being able to fritter away my words and must at all times endeavour to be consistently parsimonious with their usage.

Manufacturers Pay To Have Panels Tested By DNV-GL

DNV-GL is, among other things, a standards organization. They will test products, see how they measure up, and write up reports. But, for some strange reason, possibly communism, the people who work at DNV-GL like to be paid and so if you want them to test products you have to pay money.

This means the solar panels tested in their report were not a representative sample of solar panels in general. I suspect many manufacturers knew, or at least hoped, their panels would do well and wanted the bragging rights an independent evaluation would give them. On the other hand, there are always some panels that do really poorly in tests, so maybe some manufacturers just want to see how much they need to improve or are just really over-confident.

I suspect the internal politics of companies also plays a role at times and cruddy panels get sent for testing to convince executives to spend more money improving the product2.

But the good news is, once a manufacturer has paid to have their panels tested, DNV-GL will acquire those panels themselves. This prevents manufacturers from sending specially made, ‘golden’ panels, or scratching the label off a competitor’s product and replacing it with their own.

DNV-GL Only Reveals Who Passed Their Tests

Not what the individual scores were, or which panels failed…

For their scorecard report, DNV-GL performs 5 different, rigorous ‘torture’ tests. Manufacturers enter their panels into these tests separately, so just because a panel shows up as having passed one test doesn’t mean it underwent any other testing. DNV-GL does not even name all the panels they tested. They only reveal which ones passed the test, giving their names in alphabetical order so you can’t tell which ones did best.

But this is still useful information. Just knowing a panel passed a torture test is reassuring, even though it’s not possible to know from the result if it was the star performer or just scraped by.

The cut-off points that decide whether a panel passes or fails a test are arbitrary. There is never much difference between the worst panel that passed and the best one that failed. But that can’t be helped in this situation where the only information we are given is those that pass and none of DNV-GL’s cut-off points are unreasonable.

DNV-GL’s 5 Torture Tests

DNV GL’s 5 tests for their Module Reliability Scorecard Report are:

- Thermal Cycling — Simulates expansion from heating up in the day and contraction from cooling down at night.

- Dynamic Mechanical Load — Tests the long-term effects of wind (and potentially snow).

- Humidity-Freeze — Simulates the effects of frost.

- Damp Heat — Simulates installation in hot, humid climates, such as Darwin.

- PID — Tests how likely a panel is to degrade due to stray electrical currents.

I will tell you a little about each of these tests and which panels DNV-GL says passed, provided they are panels that are currently commonly available in Australia. If you are a manufacturer who is upset to be relegated to a footnote3 then I suggest you write me a long email in which you complain bitterly about it at length. That’s usually the best way to reach me4. I apologize5, but my goal is to succinctly present information in a way that is most useful for Australian readers. Anyone who wants all the details can follow the first link in this article, jump through one easy to navigate hoop, and download the full 31 page report.

Thermal Cycling Test

Stuff expands when it gets hot and contracts when it cools. Because different materials expand and contract at different rates, and we haven’t yet made a panel that consists of a single substance, this puts the joins between different materials under strain and can gradually cause a panel’s performance to deteriorate.

The test is done by heating a panel to 85ºC and then cooling it to -40ºC at least 600 times while passing current through it. Now that’s what I call a torture test. This should simulate 15 years of natural thermal cycling. The results are very relevant for Australia, particularly inland, away from the coasts, where the temperature difference between day and night is often extreme.

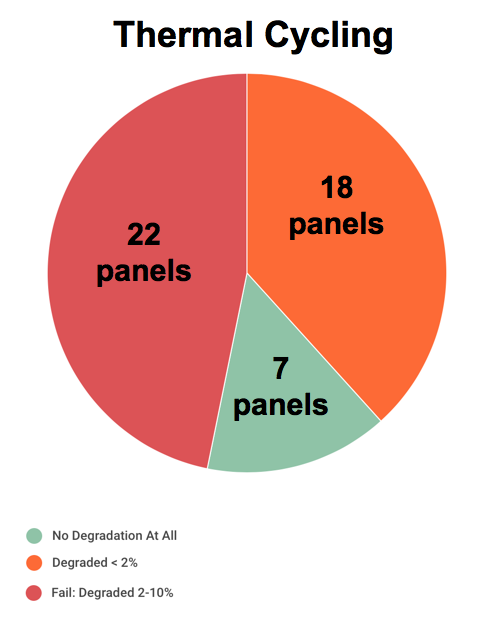

DNV-GL tested 40 different panel models. Seven panels suffered no measurable deterioration at all. Eighteen suffered less than a 2% deterioration in output still passing the test. A further 22 panels failed degrading from 2-10%.

This is a significant improvement over last year where 3% deterioration was the cut-off and even the very best panel suffered 1% deterioration.

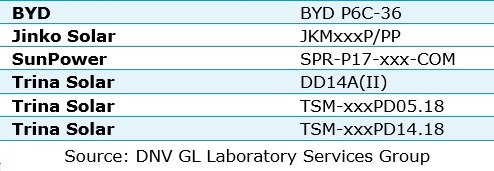

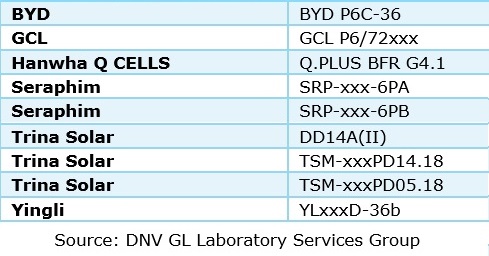

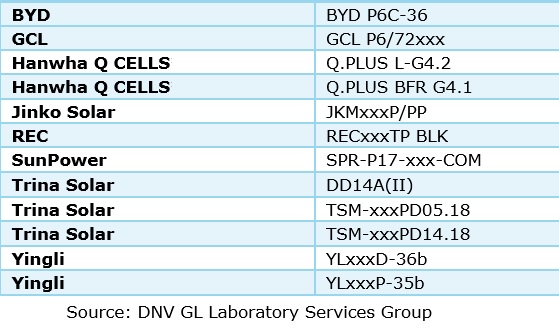

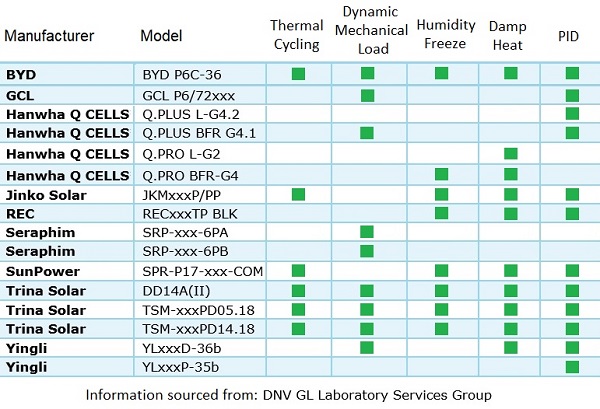

Panels that passed and are reasonably common in Australia, in alphabetical order, are:

Dynamic Mechanical Load Test

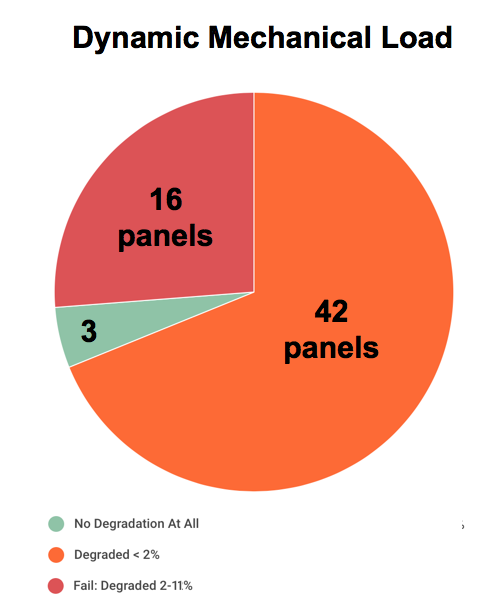

Dynamic Mechanical Load is when a load is placed on a panel that is not only mechanical, but also dynamic. In Australia it is results mostly from wind, although it can also be caused by snow. Gusts of wind blowing on panels can push them down and pull them up. The changing pressure causes panels to flex and this constant flexing can slowly cause them to degrade. A good result on this test is useful where ever there is a significant amount of wind.

A robot tests the panel, flexing it 1,000 times.

Then, just when the panel thinks its ordeal is over, it is thermally cycled 50 times as described above and then freeze cycled 10 times as described below. I told you this was torture.

Of 61 panels tested, three suffered no measurable deterioration at all. A further forty-two suffered less than 2% decline in output and were declared to have passed. Sixteen panels failed, deteriorating by 2-11%.

Among the panels that passed were the following:

Humidity-Freeze Test

If a panel is wet and its temperature drops below freezing, expanding ice can cause damage, particularly to the junction box on the back. While most of Australia can suffer from frosts, we get off lightly compared to Europe, Japan, Canada, and that country Canada wears as a pair of pants. But if you live inland you may still want to pay attention to the results of this test, as places like Canberra can still get fairly frosty. Because it is so far from the sea, Canberra suffers more frosts than Hobart.

The test consists of keeping panels in hot humid air for 20+ hours and then rapidly freezing them. This is done 30 times.

Thanks to our beautiful weather that prefers to kill us with skin cancer rather than cold, this is the test result most Australians need to worry the least about. But a good result here is can still be an indicator of overall panel quality.

Of the 33 panel models tested, 18 degraded 2.5% or less and passed. The worst panel suffered a decline of 7.6%.

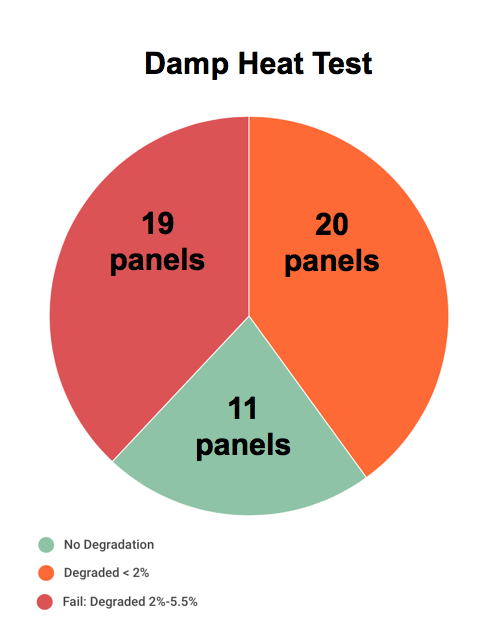

Panels that passed and can be bought in Australia are:

Damp Heat Test

While most Australians don’t have to worry too much about frost, people living in places such as Townsville and Darwin should be concerned about the Damp Heat test.

While panels may seem to be held together by their frames, those frames are really just a bow on top. What they’re mostly held together by is glue. And after enough time in a hot humid environment, that glue can come unstuck.

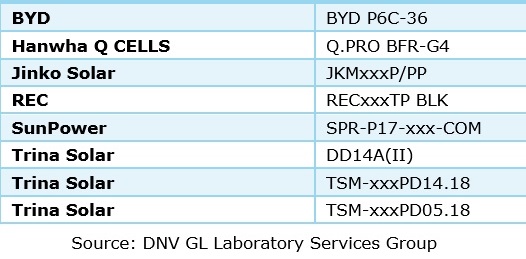

To simulate being in Darwin, panels are kept at 85% humidity and 85 degrees for 2,000 hours. Out of 42 panel models tested, 23 suffered from 1% or less deterioration and passed the test, with 11 suffering no, or next to no, deterioration in performance.

The worst performing panel degraded 5.5%. This is a huge improvement from last year’s report, where one panel’s performance declined 58.8%.

Panels that passed and can often be found knocking around Australia, or even being stationary in Australia, are:

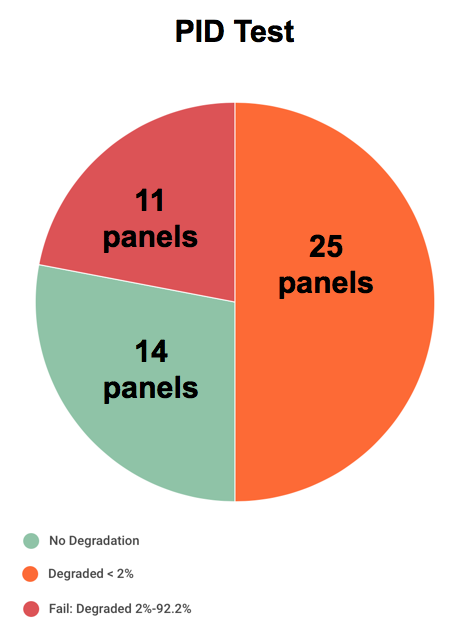

PID Test

The final test is called PID, which stands for Potential Induced Degradation. This is a type of damage that can occur due to leaking currents, including in the glass of the panel. While glass is not a good conductor of electricity, it is still possible for current to move through it and this is more likely to happen under hot, damp conditions. The test consists of replicating the Damp Heat test described above, while passing current through them for 96-100 hours6.

Out of 50 panels tested 14 had no measurable deterioration at all, a further 25 panels passed with less than 2% degradation and 11 failed the PID test.

But, of those that failed, 6 had their performance reduced by at least 10% and one of them was totally screwed with a decline of 92.2%. I wish I knew which panel that was, so I could tell you to avoid it.

If you live north of Fraser Island and you’re not far enough inland to avoid high humidity, you need panels that can pass this test. Passing panels likely to be sold in Australia are:

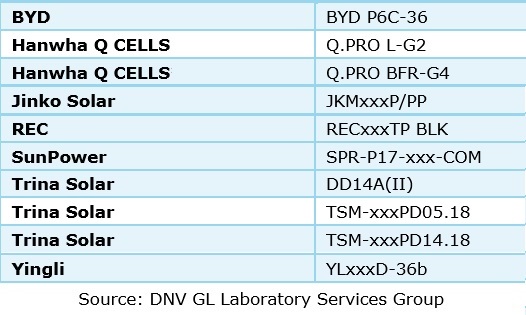

The Big Picture — Actually, It’s A Big Table

If we squish all the information on the small tables above together, it gives this:

The green squares show a panel passed a test, but if there is no green square it doesn’t mean the panel failed, because we have no way of knowing if it was actually given that particular test or not. So while we can say all three Trina panels passed every test, we can’t say they are better than the Seraphim panels because the Seraphim panels may have been given only a single test.

Big Brands Jinko And Trina Did Well

Jinko and Trina are the two largest solar panel manufacturers in the world and are known for producing panels at low prices with a 10 year product warranty that is now the industry minimum for tier one panels. As so many of their panels end up on Australian roofs, it is reassuring to see the one Jinko panel passed all four of the tests it is known to have taken while the three Trina panels passed every single test.

The only panel besides those from Trina we can be certain passed all five tests is the one from BYD. While the company is a large producer of solar panels, it is still only a small player in the Australian market.

A Panel’s Bill Of Materials Affects Reliability

Manufacturers produce different panel models and there can be considerable variation between them. Unfortunately there can also be much variation between panels that are the same model, as they are often produced in different factories using different materials. The list of components used to make a panel is called its Bill Of Materials, or BOM for short, and differences between BOMs can significantly affect reliability.

While DNV-GL can help out companies that are planning to buy millions of panels for huge solar farms and show them ones that have nice looking BOMs, their services are probably not really within the reach of someone looking to put 20 panels on their roof. All you can really do is be aware that even if a panel model tests well, there can still be inferior versions of it on the market.

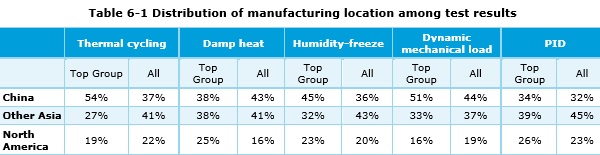

The Factory Matters And So Does The Country

In the past I would have said that it is the company that makes the panels and not the country the factory is in that’s important. But DNV-GL has provided evidence that suggests some regions do produce higher quality panels than others, with China winning out over the rest of Asia and North America, as this table shows:

As you can see, more panels that are in the “top group” of test results came from China than the rest of Asia or North America7. The only category China is beaten in is PID. This makes sense because most of China’s panels are installed in dry inland regions, while the rest of Asia tends to be more humid and so PID is more of a problem there.

The reason China does well is because it has many new production lines with up to date equipment, many robots that rarely make mistakes, and government programs that drive improved efficiency. But note that, even now, China still produces some real rubbish, including flat-out fraudulent panels, so it still pays to take care.

Standards Appear To Be Improving

DNV-GL improved the standards that panelshave to meet to pass 3 tests in this year’s report compared to last year’s. The tests were Thermal Cycling, Damp Heat, and PID. In addition more panels had no measurable deterioration in performance. While no firm conclusions can be reached from this, as DNV-GL does not test a representative sample of panels, it suggests the overall quality of panels is improving year on year.

Conclusions

While DNV-GL’s PV Module Reliability Scorecard Report does not give information on which panels failed tests or how well those that passed performed in relation to each other, being able to know that a panel did pass a particular test is still very useful. Any panel given a pass by DNV-GL can be expected to effectively withstand the real life conditions the test simulates.

Unless of course you have the bad luck to have panels that use a shoddy Bill of Materials.

Fortunately, far-sighted panel manufacturers do not want make panels that hurt their reputation and increase warranty claims. So with the help of organizations such as DNV-GL they can identify lousy BOMs, and future panel quality should become more consistent.

Just like my articles.

But please excuse me for a second while I check something…

2,649 words?

Ohshit!I’vegoneovermywordlimit!

Footnotes

- Actually, it’s been out for a couple of months, but as I spent most of June honing my sleeping skills I’m only writing about it now. ↩

- “What do you mean our panels aren’t reliable enough? Most of them are still intact by the time they leave the factory gate! If some suffer from spontaneous, energetic, disassembly upon exposure to sunlight, then we just need to spend a little more on marketing.” ↩

- I will totally remember to fill in this footnote later. ↩

- Calling me is definitely not a good way to get in touch, as the 2G network was permanently shutdown today and so my Nokia no longer works. ↩

- Eh, not really. ↩

- I don’t know why they didn’t just make it a straight 100 hours. It could be because 96 hours is 8 days. ↩

- Europe is not given as a location as Europe makes very few panels these days. ↩

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

That is a horrific cartoon. Before today, you wrote about poking eyes out.

Have you been abusing horses too?

I do everything I can to avoid abuse to horses! (Of course, sometimes it all goes disastrously wrong.)

Why do you miss Longi solar panel? They pass all 5 test!

At the time Longi didn’t have much of a presence in Australia that I was aware of. If I had known they would expand their market presence I definitely would have included them.