How to charge GST on solar is not obvious. Read on to discover why…

Let’s say you have just been quoted a nice round $7,000 for a brand spanking new rooftop solar system with 5 kilowatts of panels. With Australia’s 10% Goods and Services Tax, you might expect the GST portion of that quote to come to $700.

Or, if you didn’t go to school in Toowoomba like I did, you might actually think GST would be $636.36 because that would be 10% of $6,363.64 which would then add up to a nice round $7,000. (Remember kids, always pay attention in math class if you don’t want to end up as a lowly solar blogger.)

But, if you look at what you actually pay in GST on that quote, you will see it is likely to be over $900. WTF? That’s around 50% more you’d expect for something that costs $7,000.

But don’t worry, you’re not being ripped off. The reason why it is so high is because you have to pay GST on the full price of the system before the effect of the “solar rebate1” is applied and Small-scale Technology Certificates, or STCs, lower the price. For a $7,000 system with 5 kilowatts of panels, STCs will lower its cost by around one-third.

So if you think your installer has screwed up their quote and is overcharging you for GST, don’t panic! It is almost certainly fine. Of course, if after reading this article you realize they really have screwed up the GST, then you are allowed to panic a little if you want:

If you are willing to take me at my word that the GST amount on your rooftop solar quote is almost certainly correct, you can probably stop reading now. But if you want to find out just how STCs are calculated and be able to determine for yourself how must GST you should be paying on a solar system, feel free to read on.

How STCs Are Calculated

Working out how many STCs your solar system will receive is fairly straight forward and involves multiplying three different numbers together. These numbers are determined by:

- Location.

- Total solar panel capacity in kilowatts.

- Years left in the Small-scale Renewable Energy Scheme.

1. Location – Know Your Zone, Citizen!

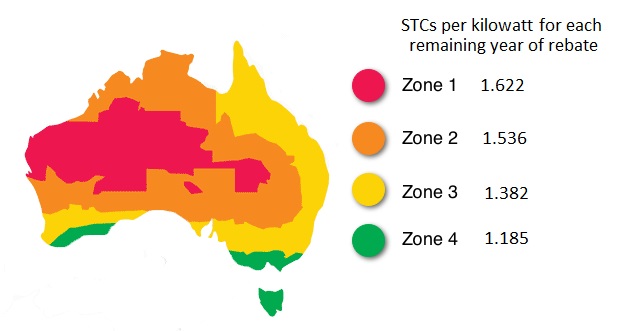

Australia is divided into four zones based on the amount of sunshine received, with sunny Alice Springs getting 37% more STCs than cloudy old Melbourne to account for the greater solar output. The image below shows the four zones and the base number of STCs received in each:

The 4 zones and how many STCs you get per kilowatt hour of solar panels for each remaining year of the Small Scale Renewable Energy Scheme (“solar rebate”).

The majority of Australians are in Zone 3 which includes Brisbane, Sydney, Canberra, Adelaide, and Perth.

2. Total Solar Panel Capacity

This number is very easy. It is simply the total capacity of all the panels in a system.

Because the number of STCs received depends on the panel capacity and not the inverter capacity, it normally makes sense to install as many panels as the inverter will allow. The total panel capacity can be a maximum of one-third larger than the inverter capacity. This means a 3 kilowatt inverter can have 4 kilowatts of panels and a 5 kilowatt inverter can have up to 6.66 kilowatts of panels. Of course, the only way you can get panels that add up to exactly 6.66 kilowatts is to win a fiddle contest with the Devil, so unless you’re the best that’s ever been, you’ll probably have to be satisfied with perhaps 6.5 kilowatts.

3. Years Left In The Small Scale Renewable Energy Scheme

The number of STCs received by rooftop solar used to be based on 15 years of solar electricity production. But, as STCs are slowing being phased out, it is now based on 14 years. On the 1st of January it will be down to 13 years. It will decrease year by year until by 2030 it will be down to one year and then the scheme will end. By that time I’ll probably be so old I won’t enjoy Justin Bieber any more and who knows how many times I will have replaced my horse called Tonto with another horse called Tonto.

Go Forth And Multiply!

After you’ve got the numbers for the zone, kilowatts of solar panels, and years left in the scheme, multiply them all together to determine how many STCs your solar system will receive.

For example, if you live in Newcastle, and are installing 6.5 kilowatts of solar panels this year, then your numbers will be:

- 1.382 for being in Zone 3.

- 6.5 for 6.5 kilowatts of solar panels

- And 14, as there are now 14 years left in the scheme in 2017. [Update: Currently in 2025 there are 6 years left.]

Multiplying these three figures together gives a total of 125.76 STCs.

Then it’s just a matter of working out how much an STC is actually worth.

STC Prices Are High Now But May Fall

The value of STCs depends on the demand for them. Currently their price is about as high as it can go. Their spot price as I write is $38.20. The highest possible amount you can get for them would be around $38.60 so they can’t get much better. While the future market for STCs doesn’t seem to indicate people are expecting a big fall in their price any time soon, it can only really go down from here, so I would say now is definitely a good time to get solar.

For our Newcastle example with 125.76 STCs, if they are worth $38.20 each, then they would reduce the cost of the solar system by $4,804. But the trouble with this is, you’re not actually going to get $38.20 each for them. Because the people who trade in certificates will want a cut and because there is uncertainly about just what the STC price will be by the time they are traded for cash, the amount you will be offered per STC will normally be a couple of dollars below the spot price and can vary between installers.

Some people may have received three quotes for solar and become concerned when they look at them because they have been given three different figures for the price of STCs. But all it probably means is the installers trade STCs in different ways and so offer slightly different amounts for them.

The STC Price Doesn’t Really Matter

While the price offered for STCs may seem an important consideration for people trying to decide between different quotes, it actually isn’t. While the higher the STC price, the more the total cost of the solar panel system will be reduced, the only thing that really matters for the customer is the final price they need to pay.

If a customer had to choose between 3 identical systems offered by 3 equally skilled and equally ethical installers, it wouldn’t matter what price they offered for STCs, because only the final installation price would be important from the customer’s point of view.

That said, if a quote has a price for STCs that is excessively low, then perhaps a mistake has been made, or possibly the installer is trying to reduce the amount of GST they need to pay in a naughty way.

How To Calculate GST On A Solar System

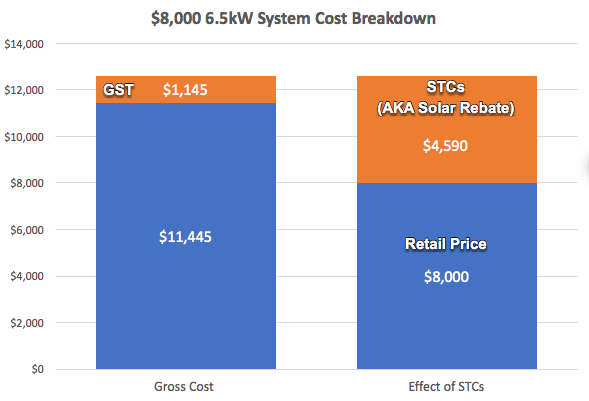

If the people in the Newcastle example who are installing a system with 6.5 kilowatts of solar panels this year are offered $36.50 per STC by an installer, which is $1.70 less than the spot price, then with their 125.76 STCs the cost of their system for them would be lowered by $4,590.

If what they have to pay for the system is a nice round $8,000 then the total cost before STCs are applied would be $12,590. This means the STCs would reduce the price by 36%.

To work out how much of that would be GST, take out a pencil and paper and use it to divide the total cost by 11. If you don’t have a paper and pencil you can use a calculator or you could just ask Siri. (But not that bitch Alexa. I still haven’t forgiven her for what she said about Cortana.)

Dividing the total cost of $12,590 by 11 gives a GST of $1,145.

Here’s how the Gross Cost, GST, STCs and Retail Price all fit together.

If you divide the total cost by 11 and the result is different from the amount of GST on the quote, then either a mistake has been made, or you are dealing with a total shonk.

The last word: Beware of solar companies that miscalculate GST

Solar companies who miscalculate GST on solar should be pretty rare these days, but apparently they are still around, so be on your toes if this happens. Sure, it could be an honest mistake, but it could also be a dishonest one.

Footnotes

- The solar rebate is technically not a rebate, but certainly seems like one. As that’s what people have decided to call it, we’re kind of stuck with the term. ↩

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

I have three phase input to my house with two separate systems of 5kw of solar panels on two separate inverters (sma) and was looking at the following options: 1. Adding another system and inverter to the third phase or 2. Changing the two inverters over for one three phase or 3.Changing my aircon unit for single phase. My goal in 1-2 years is to have battery back up. What is your suggestion?

Hi John. If the new Australian Standards as described here:

https://www.solarquotes.com.au/blog/powerwall-2-as4777/

Apply in your area, then if you want to AC couple batteries you will need to leave one phase free and then you could add AC coupled batteries with up to 5 kilowatts of battery inverter. But this is far from an optimal solution as the batteries could only supply power to the phase they are on and the loads that are connected to it.

Getting a 3 phase inverter would get around this problem as then you could have 15 kilowatts of solar inverter in total and as much battery capacity as desired.

Changing your air conditioner from 3 phase to single phase shouldn’t make a difference.

My advice is to wait and see what your local network operator says is permissible in your area. If you decide to get a new 3 phase inverter, there is no point in getting one until you are ready to install batteries, unless you are certain you want batteries and you are also eager to increase your rooftop solar capacity in the meantime.

Thanks for the response. I am keen to go down the battery route but my understanding us that there are limited battery storage options for three phase residential and what is available is at a premium price.

That sums it up pretty well. One option would be to use a DC converter to attach batteries, but that has its own limitations. I wrote about using the Goodwe GW2500-BP to do that here:

https://www.solarquotes.com.au/blog/goodwe-bp/

Ronald. Over the last 6 quarters I used 6000 KWh, of which 2400KWh was for off-peak water heating. I generated 2900KWh. I was getting 60c lead-in tariff. Now I get just 6c lead-in tariff. I don’t want to pay around $700 for a smart meter and pay for timers to run my dishwasher etc during the hours that I _hope_ the sun will shine. I’d rather just push all the power into my hot water heater and run dishwasher/washing machine overnight. Then I know I won’t be wasting Peak electricity if it’s cloudy. Questions: 1) Is this sensible? 2) Is this feasible – what would happen to power generated from the PV panels if the water heater was up to temperature?

Hello Harry. It is possible to have any excess power produced by your solar panels sent to your hot water system, but this would require a diverter and that would be expensive to get installed. If you did have a diverter and the hot water was up to temperature the excess electricity would be sent into the grid.

One option would be to leave your hot water on off-peak power and get a smart meter, but not get a time-of-use tariff. Using a standard tariff is usually best for people who have solar and there is no requirement to be on a time-of-use tariff if you have smart meter. This way you’d pay a lower rate for hot water and wouldn’t have to pay a high peak rate in the evening after your solar system has stopped producing electricity.

Another option would be to get a larger solar system. If you generated 2,900 kilowatt-hours over 18 months then I am guessing you have a small 1.5 kilowatt system. With a larger system you would normally be able to generate enough solar electricity for your hot water system whether you used a diverter or a timer. If you want to avoid spending money at the moment this obviously won’t be a good solution for you, but it could definitely could pay off in the long run.

..or install a Hot water solar system.

The GST rip off is ripe in the industry!

So far 80% of invoices I’ve seen list one line price that the clients pays and shows the GST only on discounted price. There is iether no mention of RECs / STC price as a line item or its just a noted entry not calculated.

This means companies are paying up to $400 per system less in GST so no wonder their price is cheaper.

Think about that!!!

500 systems a week in Australia at $400 each!! GST rip off or think of it as schools, roads, hospitals and services we don’t get.