There are so few EVs on Australian roads, I had to badly Photoshop one onto this picture.

As I write this, approximately 1 in 10 new cars sold worldwide are electric. But not in Australia. Here it’s little more than 1 in 50. That’s a large difference and it’s not because we regularly drive beyond the black stump. Australia is more urbanized than Germany and, on average, we drive our cars fewer kilometres than they do. Most Australian families keep at least one vehicle well within the black stump.

Our lack of EVs also is not because we don’t want them. Plenty of Australians want an electric car. They just have trouble getting them. Electric vehicles are either available in limited numbers far below demand or have waiting periods that can be over a year depending on the model. While some conventional cars currently have long waiting periods, for EVs they’re far worse.

This comes down to Government policy. (Boo! Hiss!).

Not only have we been slow to introduce incentives, but we’ve also been quick to introduce disincentives. Despite this, Australian EV sales tripled last year. They are now just over 2% of new car sales and I expect this figure will increase rapidly. I also think uptake won’t just mirror that of other countries, but we’ll start to catch up.

In this post, I’ll tell you what’s happening with EVs in the rest of the world and why Australia lags so far behind.

Tesla doesn’t have a reputation for getting things done on time, so if you order a Tesla Model 3 on the same day you get pregnant, I’d say it’s 50-50 you’ll be driving bub home from the hospital on electric power.

World EV Production

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has published a report on the current state of EVs that you can check out here. There’s no need to be scared of it. It’s not 260 pages long like most IEA reports. It’s only a single page. Admittedly, to get to the bottom of that page you have to scroll down around 30 metres — but it’s still, technically, only one page.

In the report1 they estimate there are 16 million EVs on the road today. These electric vehicles should have reduced world oil consumption and CO2 emissions, but increased sales of ICE (Internal Combustion Engine) SUVs cancelled it out.

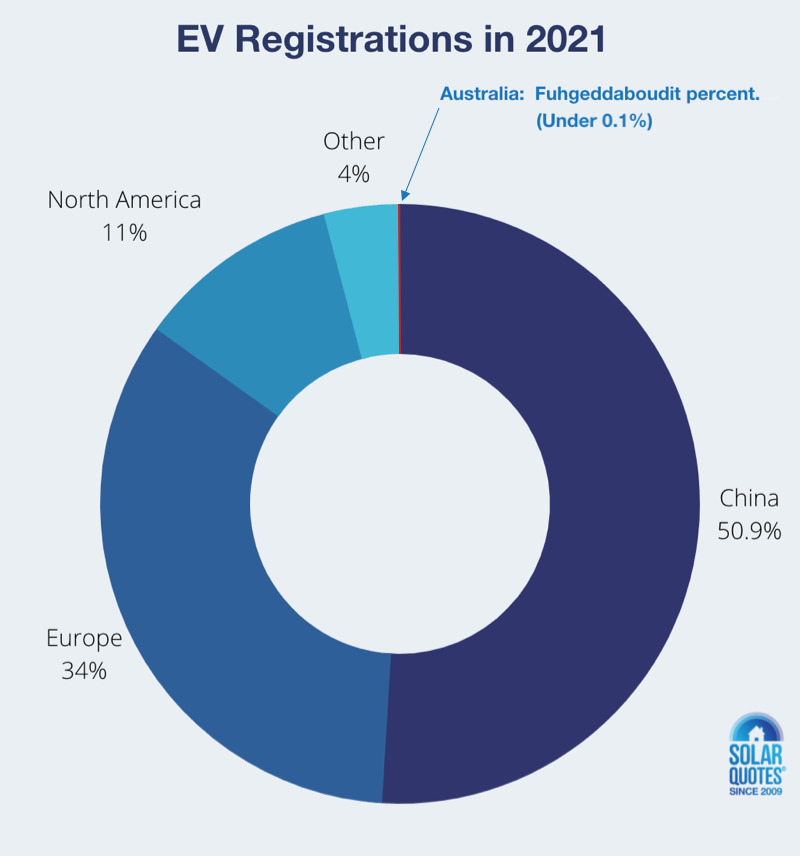

Last year 6.6 million new EVs were registered. By region, the percentages were:

As you can see, China really doesn’t want to be dependent on imported oil, no matter what countries it comes from.

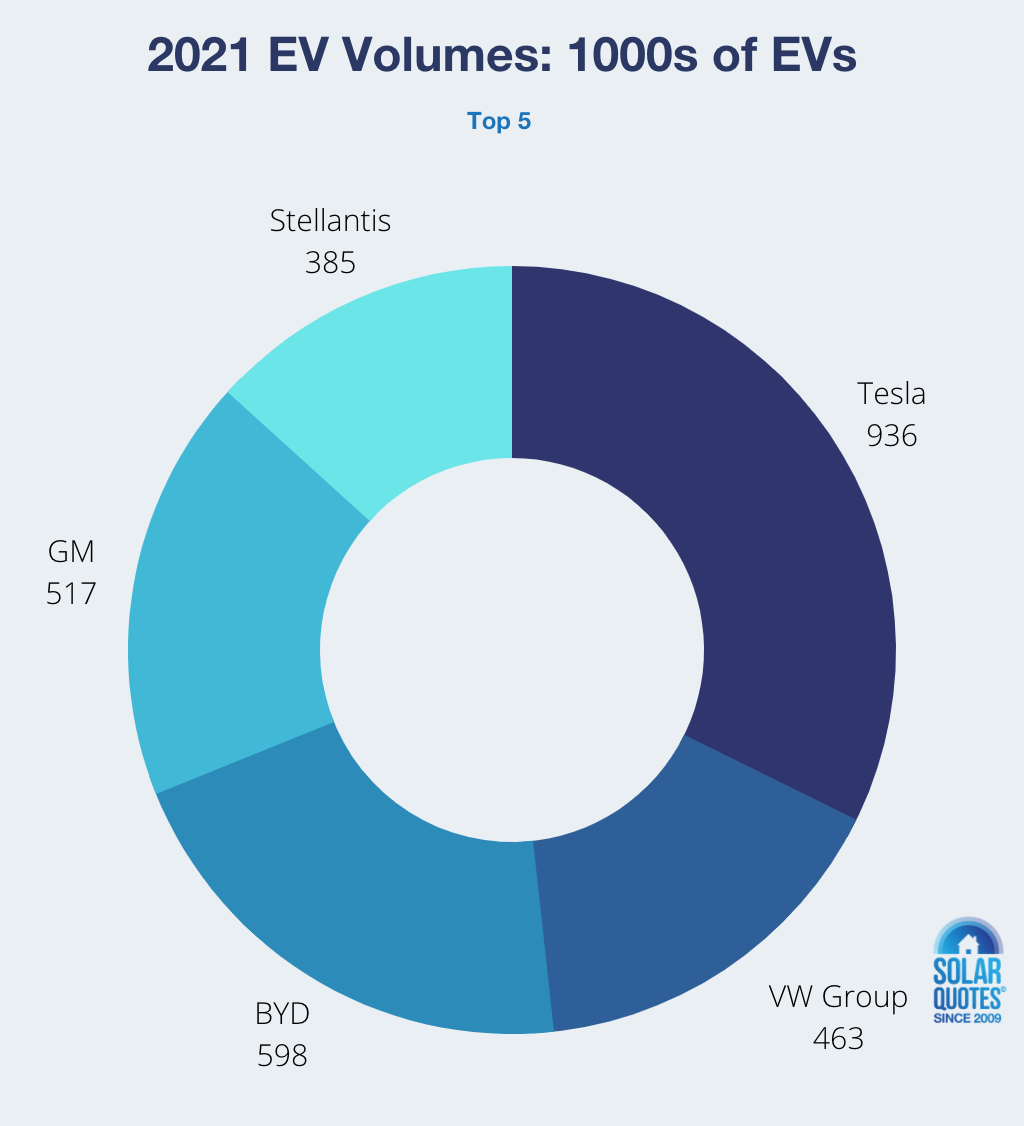

Here are the five largest manufacturers:

In case you are wondering what the hell Stellantis is, they are these guys here. It’s a new company Frankensteined together last year and is the 6th largest automobile maker in the world.

EV Extrapolation

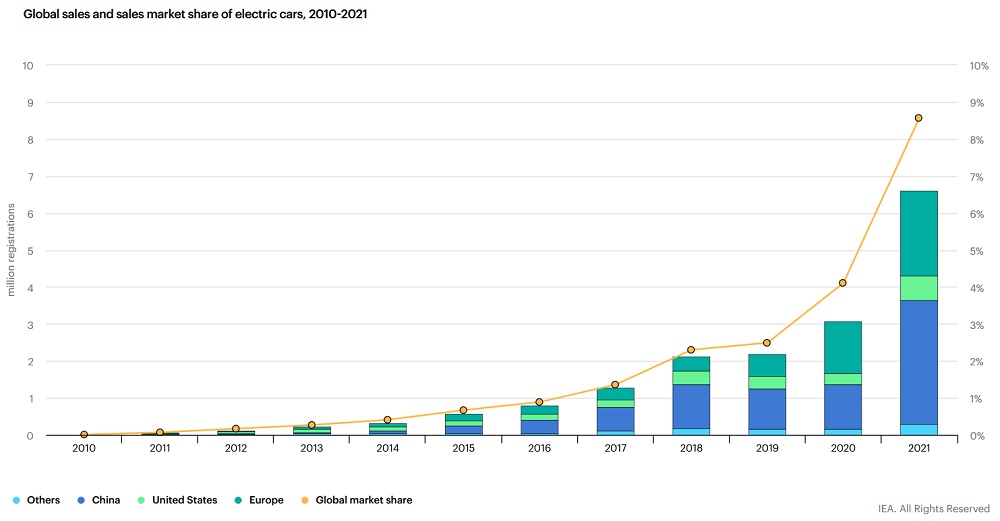

Here’s a graph from the IEA EV analysis showing worldwide figures for how many millions of electric cars were registered from 2010 to 2021. It also shows them as a percentage of total new car sales:

Looking at global market share, six years ago EVs were 1% of new car sales. In 2021 they were 8.7%. This is a very rapid expansion. Over the past 10 years, the annual growth rate was over 50%. At this rate electric vehicles will be around 13.5% of new car sales this year and, right now, they should be around 10%.

If this expansion continues — which it won’t — EVs will reach 100% of new car sales in 2027.

Since new car sales aren’t going to go all-electric in just five years’ time, the growth in the percentage of EV new car sales is probably not what we should consider2.

Looking at actual EV production should be more informative. This was 6.6 million vehicles in 2021 — more than twice as many as in 2020. Over the past 10 years, EVs’ annual growth rate was around 50%. If this continues in 2027, 75 million electric vehicles will be built. The world made 75 million vehicles in 2019, a record year. Allowing for some increased demand means all new cars will be EVs in 2028 — provided the trend continues.

I’m not saying EV production will grow this rapidly and I don’t think it will. But there is potential for rapid expansion.

Adoption Rate

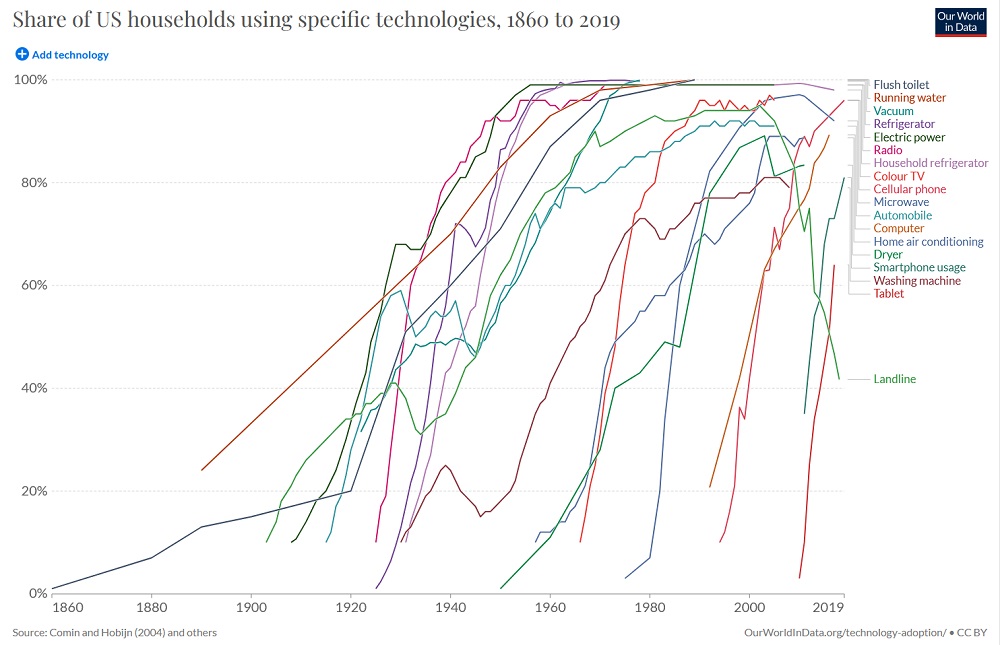

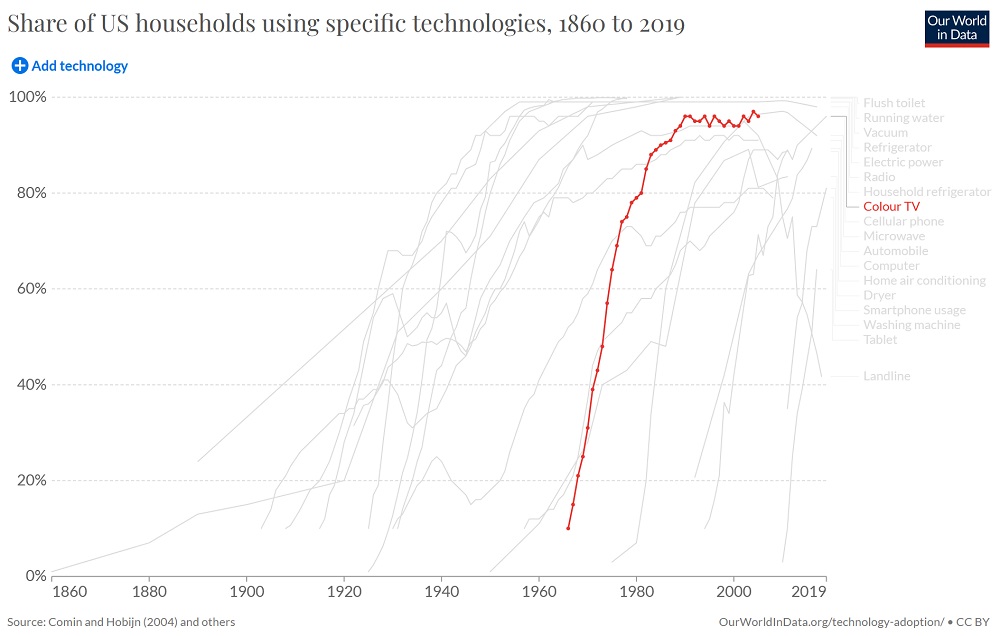

Just because I can extrapolate current trends into the future doesn’t mean they’ll actually happen. Technological adoption doesn’t work that way. Instead, it tends to work almost that way, as this graph of US household uptake of new technology shows:

Years ago this graph was considered really cool and it turned up in all sorts of places. Lately it has been neglected, but I thought I’d get its hopes up by giving it a shot at getting trendy again.

The graph shows Americans embraced many technologies rapidly. But I can think of several reasons why consumers won’t adopt electric cars as quickly as radios or microwaves:

- Electric cars still cost considerably more than lower-cost conventional cars.

- Vehicles last a long time and are only replaced gradually.

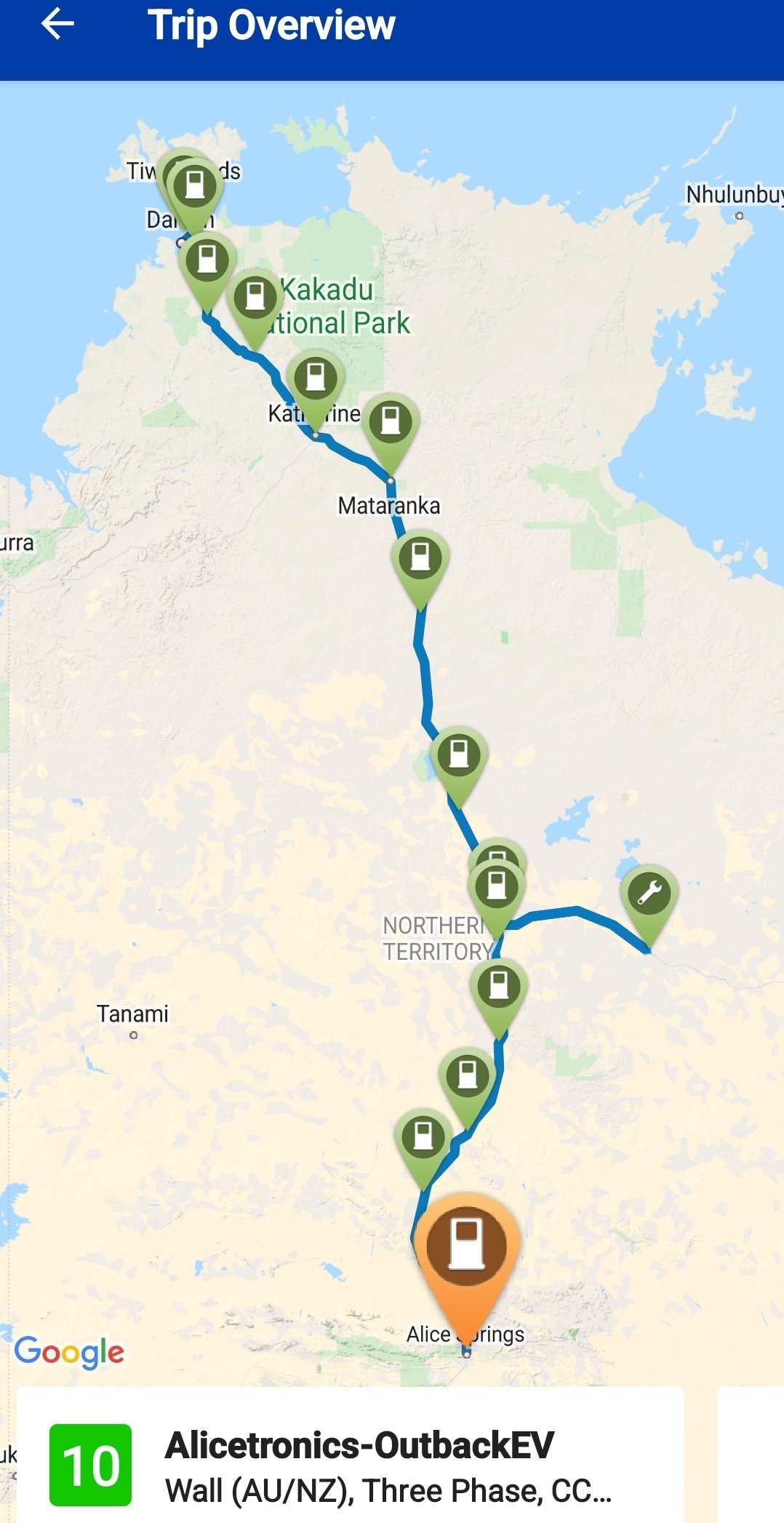

- EVs aren’t as suitable for driving crazy-long distances through the outback — especially if a course is carefully plotted to avoid all fast chargers.

But I don’t think any of them are very convincing.

Let’s take a look at just one item on the graph above — colour TVs:

In the US, colour television took off in the second half of the 60s once over 50% of broadcasts were in colour. By the end of the 70s around 90% of homes had at least one television.

But no one had a pressing need for a colour TV:

- Everyone already had a black and white TV3 or at least a radio.

- Colour TVs were very expensive. In Australia, in 1975 they were around $1,100-$1,300 which was about 8 weeks’ average full-time earnings.

The only thing colour TV had going for it was the fact it was better than black and white. But that was enough. After colour transmission was introduced here in March 1975 it was only three years before 70% of homes in Sydney and 64% in Melbourne had colour TVs.

The only thing EVs have going from them — for the large majority of Australians — is they are better than conventional cars. Their performance is superior to similar priced internal combustion engine vehicles and they’re far cheaper to run. At the moment, new electric vehicles are only available in the mid and upper price ranges, but this will change.

Why So Few Oz EVs?

There are four main reasons why electric car sales have been so low here compared to other developed countries:

- Low petrol and diesel prices by world standards. (But our low average fuel efficiency means Australians can save a lot on fuel by going electric.)

- Until recently, there was little in the way of incentives or subsidies to encourage people to get electric cars. Now there are incentives, but they’re still little compared to many other well-off countries.

- We’re the only country to already have an EV disincentive in place — the Victorian EV road tax — with more planned for the future.

- No fuel efficiency standards.

The largest contributor to a low EV uptake is the last on the list — our lack of fuel efficiency standards. As far as I know, Australia is the only developed country without any fuel efficiency requirements. Because of this, Australian cars now consume nearly twice as much fuel per km as in Europe.

Labor tried to introduce fuel efficiency standards last election but Scott Morrison said they would destroy the weekend. This piece of brilliance saved us from having two days of the week obliterated from the calendar, as happened in Europe, North America, Japan, and everywhere else cars average over 10 km per litre.

Because other countries have fuel efficiency standards, they have an incentive to keep EVs for themselves rather than send them to Australia. But there is good news. Because EV production is increasing so rapidly, other countries should have little difficulty meeting their standards in the future, so more EVs should soon be available here.

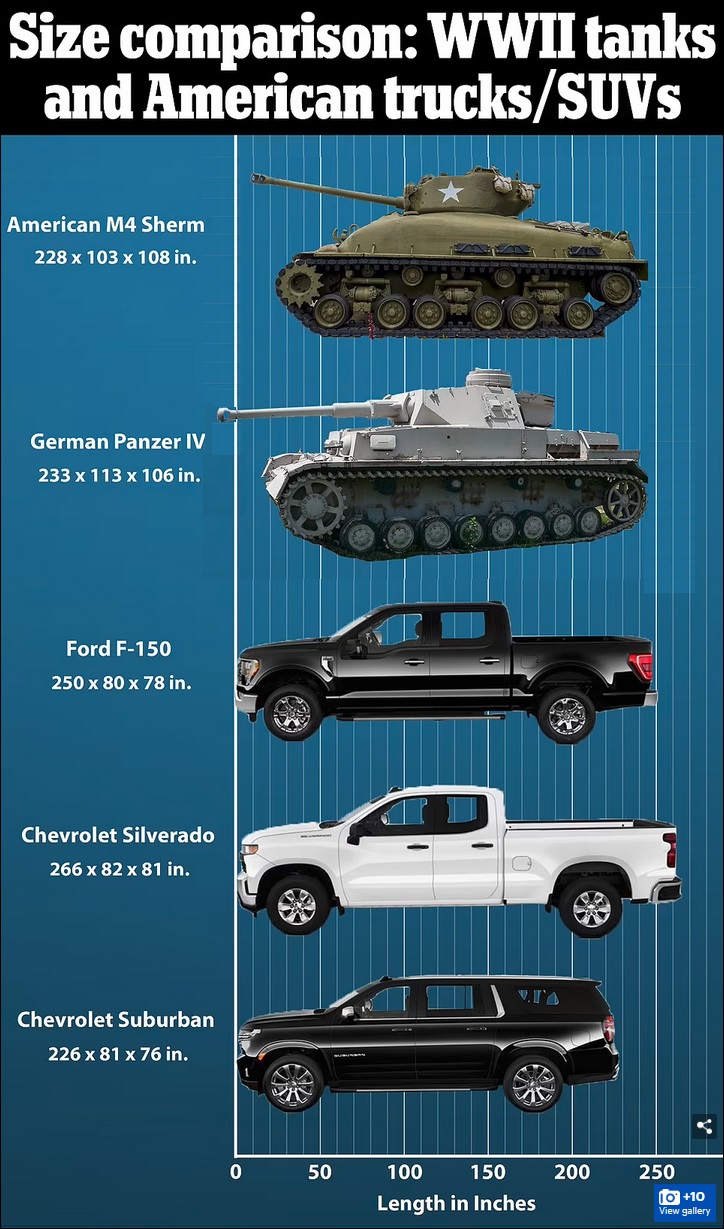

Up until now, the global car industry was using the fuel efficiency benefits of electric vehicles to build more petrol and diesel guzzling SUVs. They also built ridiculous oversized trucks for American men who want to compensate for the fact their current truck isn’t the size of a Sherman tank:

Image: Daily Mail (But note I flipped the tanks because they were facing the wrong way. They’ve been doing a lot in Ukraine lately, so I figured it would be okay.)

But thanks to the run-up in oil prices resulting from Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, I expect people will now be much more focused on fuel efficiency and even more interested in EVs.

A Psychological Problem

There’s also a fourth reason for our low EV uptake that’s psychological. A large number of Australians are convinced they are coiled springs poised to suddenly leap into their cars and surrender to the urge to drive across the outback and start chucking laps around Uluru. This is common even if the last time the deluded person saw a kangaroo was when they bought a dodgy meat pie.

While there are definitely some people who drive crazy long distances in the outback, for most Australians EV benefits far outweigh any disadvantages. Because electric cars can be plugged in at home, most people will spend less time on charging than they currently spend at the servo. Families with two or more cars will also find it easy to get one EV and then decide if they want to go all-electric.

As for people in remote locations, I strongly suspect that as EV rapid chargers become more common and charging times faster, people who regularly drive long distances will rush to buy electric vehicles to save on fuel costs. These savings will grow as solar energy falls further in cost.

Even today – with patience and a plan, it is possible to do some pretty remote trips in an EV and it’s only going to get easier as charging infrastructure improves.

Image: Outback EV Hunter

We’re Getting There

With sales tripling in 2021 from the year before, EVs are clearly taking off in Australia. Hopefully, they’ll go from just over 2% of new vehicle sales last year to over 5% this year. This will depend on availability, but thanks to the recent run-up in oil prices, I expect we’ll see more demand and more electric cars offered for sale here. After a very slow start, Australia’s EV revolution is underway.

In my optimistic vision of the future, Australia’s post-apocalyptic wasteland raiders will drive electric mutant mobiles and shoot lightning from their guitars.

Footnotes

- They don’t call it a report. They refer to it as an “analysis”. I think the difference is, when you print out a hard copy of an IEA analysis it’s easy to hold in one hand, while if you print out a report it’s hefty enough to use as a murder weapon. ↩

- One drawback is it’s affected by changes in conventional car sales. For example, thanks to COVID, sales of all cars in 2020 were 15% lower than in 2019. This bumped up EVs’ sales percentage, but the effect will disappear now the slowdown in conventional car production is nearly over. ↩

- Even after we got colour TV here they kept playing the Black and White Minstrel Show for a full three years. If you don’t know what that was, you can follow this link, but for god’s sake, don’t watch it all at once. If you were born after the 70s it will kill you. ↩

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

I drove 300 kilometres in my model 3 yesterday, (and mostly on autopilot), in Airconditioned comfort and listening to some really great music.

It cost me around $7.60 in electricity. (16c/kWh on night rate off peak.)

(Sadly I’ll be doing the same next week to attend a funeral of a good friend.)

Is it any wonder that I absolutely love the car?

Is it that China doesn’t want to be reliant on imported oil, or for another reason such as the government wants to know where all its residents are at all times, that air pollution in most (all?) of their cities is so bad that they need to adopt radical measures such as shifting from ICEVs to EVs, or something else? Of course the self proclaimed Middle Kingdom could always have a combination of reasons.

There’s one thing not talked about much is what’s common in many households these days is to have multiple cars. Kids are staying at home longer for example and they have a car each.

My neighbours to one side and two homes opposite for example each have 7 cars. Yes 7 in a household.

That might be the extreme but its pretty common to see homes with at least 3-4 cars.

Question is, how do you charge 7 cars in a household? Even if you only charge half of them on alternate nights, you have a shortfall. Or even 2 each 3 days to keep them topped up.

Apart from the above I think the major reason for low sales is EV’s is simply cost. No matter how you put it, EV’s cost much more. A newly licenced car buyer is looking at the low end if they buy a NEW car. Typically under $22k I imagine What do you tell them….. wait with no car until you save up enough for a new EV? .

Not to mention the cost of replacing the batteries. Almost the cost of the car.

In China, BYD is warranting their LFP blade batteries for half a million km, I’ve read. That would be beyond the service life of an ICE vehicle, and perhaps even an EV. The battery capacity is warranted to be 80% at that point, allowing vehicle demotion to local commutes, battery resale for use in domestic energy storage or EV ride-on mowers, etc. Here, the same vehicles’ batteries are only being warranted to 160,000 km, which is only ten years average use. Is the Tesla warranty better?

Automotive spare parts prices have always been a bit of a rort, but the answer is already in use overseas. Pay a fraction for a small company for an equivalent, but by then higher capacity, longer range, more modern technology replacement, _if_ you’re a travelling salesman and manage to wear out the battery, flogging it with fast charges.

My plan is to ensure my commute EV will have at least 100% more range than needed, something that most have already, then if range drops by 40% after 320,000 km, then I’d have to change the battery after three or four decades or more. If I wear it out in off-grid V2H use, then it’s still a dead set money saver when a $45k EV equals at least 5 Tesla Powerwalls, which would cost $75k. I.e. the car has cost negative $30k in that equation, and has zero fuel costs, saving even more money every week. (And yes, it would cost more than $75k to connect to the grid. Zero chance off that happening.)

In a commute EV, there is every chance that the battery will outlast the vehicle’s useful life. Especially in a five or seven vehicle household, a long range regular interstate highway thrasher will naturally be passed on to a more local commuter after many years of use. The battery can then outlast the vehicle.

And in a single vehicle household with long range needs, an EV down to 80% of range will have a very good resale value. In a decade, a tired ICEV will only have scrap iron value – that is unavoidable.

A modular battery, able to be disassembled, is a necessity, I feel. Any vehicle component can suffer a fault after years of use. A battery pack in which all the cells are bonded to the top and bottom laminae to form a structural member is unlikely to be repairable. Some Teslas are built this way, according to reports. Cutting manufacturing costs isn’t everything.

We are retired farmers who live in a rural location. Almost all of our travel is in rural and remote areas. When travelling in remote areas we tow an off road caravan. Currently there are no electric vehicles on the market that have sufficient range to get to many of our destinations, let alone back again.

Consider also farm machinery, an electric solution does not exist for any seriously sized machinery.

Perhaps Hydrogen as a fuel is a solution.

The staggering investment in capital and engineering effort to rapid-build the factories to manufacture the millions of EVs is eye-popping. Not just Tesla’s two new Gigafactories (Texas & Berlin), but BYD’s ICE factory conversion and new factory under construction. At 6 billion USD, going to 10 billion when fully kitted out for over 1 million EVs per factory per year, it’s handy that Tesla reported 27.5% gross profit per vehicle the month before last, to pay for it all. Mind you, a market capitalisation exceeding the value of the next nine global auto manufacturers combined has to provide some financing momentum. At 1.6 km x 400m (with 7 floors, I’ve heard), the GigaTexas building has more indoor area than our farm has outdoors.

Cranking up the two new factories from their very recent production starts will take time, so Tesla’s last year’s 936,000 EVs is only projected to grow to 2 million this year. Will that only grow to 3 million next year, as there’s no additional factory under construction so far?

BYD’s soaring EV production is a superb run chase, and the new factory should allow a catch up. But they intend to overtake. They have 7 battery factories, and are building an eighth. That’s arguably less than Tesla’s battery and lithium sourcing efforts, including a 4 year contract with the new mine in W.A. It’s just an enormous pity that a substantial portion of BYD’s output is hybrids.

Legacy manufacturers converting to EVs have unsuited factories, and largely each rely on a single supplier of Li-ion batteries requiring nickel and cobalt. Nickel prices have skyrocketed (tripled?) with demand, and supply will be insufficient. BYD uses its own LFP batteries (no nickel, no cobalt), and Tesla is switching. Will the new sodium-ion batteries, now achieving competitive capacity figures, be the competitive edge by 2026?

Ford is splitting its ICE and EV businesses so it can thrash the former in an unmaintained cash generation burn, in an attempt to phoenix a viable EV manufacturing business out of the ashes. VW is building a greenfield EV plant, having learnt that converted ICE plants are not competitive. Their ambition to catch up with Tesla by 2027 is probably not achievable, especially given their lower profitability and enormous debt burden. If GM exists in 2030, will it be any more than a shareholding in their joint ventures in China? That’s the only place they make more than a few hundred EVs, and many of them are hybrids, if memory serves. Volvo is just a Chinese brand name now. The Polestar 2 is a nice vehicle.

At A$45k drive-away, the BYD Atto 3 is the beginning of EV competitiveness in Australia, I think. My sister has one on order, but mad demand up north is not doing much to help timely delivery down under, I sense. At least RH drive has its own production line at BYD, I hear. (Will the nifty Xpeng P5 be available here by the time I can make the switch, next year?. … Oops, forgot, it doesn’t have the safer LFP batteries.) And I will require V2H. Its contribution to rural off-grid autonomy is equivalent to 5 to 7 Tesla powerwalls, “for free”, so not to be sneezed at in my book. It’s a game changer – no more need to wait for a repurposed ex-EV battery pack to become available when you can use the one in your EV for both purposes.

It seems to be a great time for holding on to an ageing ICE vehicle for another year or two while EVs become more available in these backwoods. The only financially fatal mistake would be buying an ICE vehicle. Zero trade-in value in a few years, and a fuel cost black hole of increasingly stygian depths.

Erik Christiansen,

“It seems to be a great time for holding on to an ageing ICE vehicle for another year or two while EVs become more available in these backwoods.”

It depends on how fuel prices (and supplies) may behave over “another year or two”.

Meanwhile, global diesel fuel production is declining significantly, well before the coronavirus pandemic, and now resulting in diesel shortages in Europe (and potentially fuel rationing soon). See the Spanish post, translated into English titled The diesel peak: 2021 edition., published on 19 Nov 2021, and scroll down below the sub-heading the diesel to view the graph of global gas oil and diesel production.

https://crashoil.blogspot.com/2021/11/el-pico-del-diesel-edicion-de-2021.html

Per S&P Global Commodity Insights, dated Apr 2, in an article by Rosemary Griffin headlined Russia delays publication of March oil output, export data, it includes:

https://www.spglobal.com/commodity-insights/en/market-insights/latest-news/oil/040222-russia-delays-publication-of-march-oil-output-export-data

Per EIA, US stocks of crude oil in the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) were at 588,317,000 barrels at the end of Jan 2022.

https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=PET&s=MCSSTUS1&f=M

Starting in May, the United States will release 1 million barrels per day (bpd) of crude oil for six months from the SPR.

https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/biden-release-1-mln-barrels-oil-day-ease-pump-prices-2022-03-31/

A 180 million barrel release from the US SPR represents nearly one-third of its current inventory. What if that isn’t enough to lower fuel prices? Time will tell.

How are the sales of e-bikes going? That what we should be promoting the use of, not more cars.

Good idea. My next EV review should be an e-bike.

E-bikes, the transport choice of champions!

Er what’s an e-bike? Do you mean a motorcycle as opposed to a bicycle? Peddle power is already environmentally friendly so … 😛

Subsidies come from us taxpayers, even if they come via a government program. So when EVs really of themselves, are more economical than conventionally fuelled vehicles and cheaper to buy, they will become very popular. In the meantime, only people who think government subsidies don’t come from taxpayers will be silly or wealthy enough to be interested..

I’m not a big fan of subsidies for EVs. I’m a fan of making internal combustion engine vehicles pay for their externalities, which mostly isn’t happening at the moment.

You all (that sounds very yankee hillbilly) should perhaps view this, which, if the pretend greens (“You must eat your greens!”) party were genuine, would demand for Australia, before guaranteeing confidence and supply…

https://www.nzta.govt.nz/vehicles/clean-car-programme/clean-car-discount/overview/

Of course, the discounting/rebates should apply only to fully Battery Electric Vehicles, and, not to “hybrid” vehicles, and, the levies on ICE vehicles, should not be capped, but, should be proportional to the emissions.

And, Australia should have nationwide mandatory roadworthiness testing, including emissions monitoring, so registration fees could be proportional to emissions levels (plus a fixed licensing fee).

And, because of the pillaging of revenue from fuel excise fees, that is supposed to be for roads development and maintenance, all vehicles should be required to be charged additional road usage fees, as part of the registration fees, as, I believe, is done in NZ for diesel fuelled vehicles (and, the Australian fraudulently charged roadworks component, removed from fuel excise fees).

Hi clicked on the stellantis link and read up , they cant get enough semiconductors to make their cars so I looked them up do you have any idea how much water is used to make these 2200 gallons per 300mm wafer circuit , and the pollutants for the process and large amounts of energy . In the end trying to go green in truth is an oxy moron . sorry don’t want to be a downer

Depending on the chip there may be 600 per 300mm wafer, so that would be 3.7 gallons of water per chip. That sounds a lot better, but water use is still a consideration.

There is another factor. Whistle blowers have indicated that the traditional automakers are intentionally dragging their feet. Dealers are trained to talk punters out of considering EV, and the Kia EV6 has a waiting list until 2025 (!).

EVs are too cheap to service so would terminate a traditional source of after-sales revenue. Only one automaker stands to benefit from EVs, you can guess which one.

Dealers are becoming an endangered species. Tesla does not have them, Ford is working on eliminating them, and BYDs can be ordered on the internet. If repair shops can efficiently source replacement parts, then an open repair market should maximise competition. Manufacturers clinging to dealers may rapidly lose market share, at least amongst informed buyers.

If ICEVs need a service every 15,000 km, then an EV may benefit from one every 50,000 km. Certainly any warranty-mandated period should not be less than that, other than when the service report says “Brake pads only good for 10,000 km more.” That’s a good reason for preferring an EV with several settings for regenerative braking on accelerator back-off.

We need to be alert to the creeping “Service Economy” model of fabricating employment. At the beginning of my recent owner-build, I had to pay a town planner over $2k just to reformat my fire plan submission, before the CFA would accept it. The substance of the reformat differed only in that it offered less defensive area than the original. Totally superfluous frequent inspections of EVs would be similarly unproductive … but lucrative.