Image Credit: Glen Morris. Typeface & Design Credit: Beelzebub & his helpers from Standards Australia.

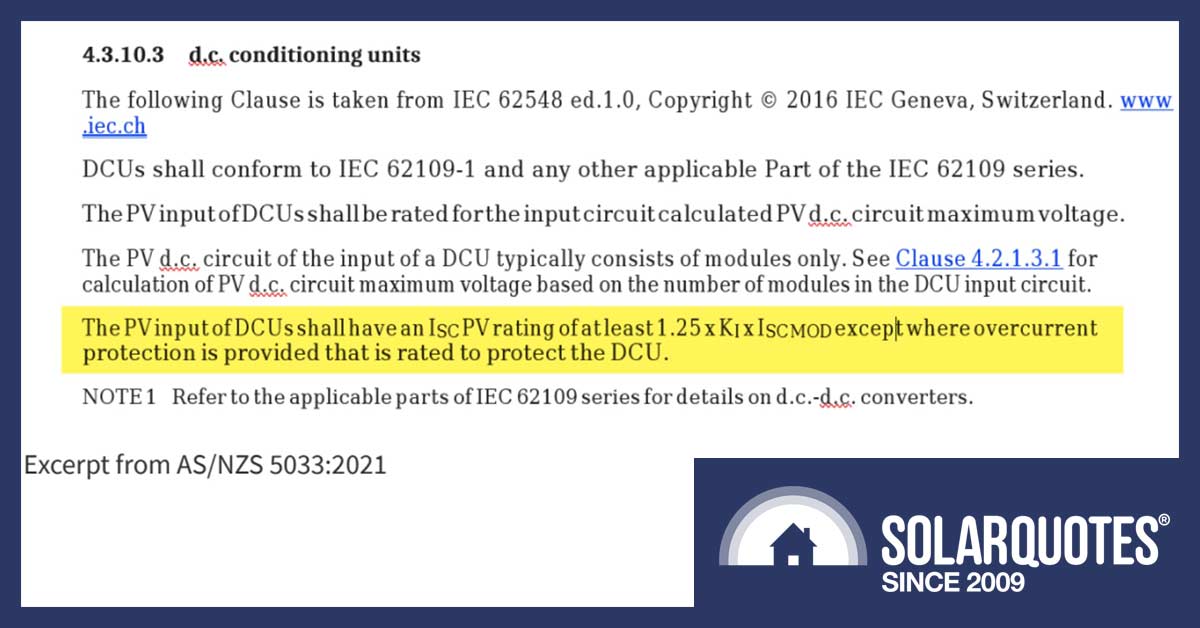

The recently updated Australian Standard for solar installations, AS5033:2021, contains the following clause that has caused a few headaches for solar installers and designers:

The PV input of DCU1s shall have an ISC PV rating of at least 1.25 x KI x ISCMOD except where overcurrent protection is provided that is rated to protect the DCU.

Translation: the solar inverter used on the solar system can’t just be rated to the calculated maximum current from the solar panels. It must be rated to 1.25x that current. This can be challenging when using modern, high-power, high-current solar panels with the solar inverters currently on the Australian market.

For those who’ve been in the industry long enough, this is just the latest dip and turn of the SolarCoaster. It seems there’s not a week that goes by without some insensible regulatory change, adhoc government policy or economic challenge with the potential to make those without a solar-strength constitution lose their lunch.

On that note, I have noticed a few electrical contractors “getting out of solar” recently, offering job lots of leftover stock, selling panel-lifting machines and edge protection/scaffold. The onerous compliance is getting to some people, and they’re just going back to air conditioning installs.

This episode of standards pearl-clutching is a little different though, because AS5033 has been updated for 2021, and it’s only now we’ve collectively realised a clause that was there since 2012. Unnoticed in the past, it’s now causing some heartache. Except perhaps for the Fronius fanbois, they’re in love all over again.

Inverters Playing Catchup With More Powerful Panels

There has been a collision between the incredibly wonderful Australian Standards and the international solar energy industry. As solar panels become ever larger, more efficient and more powerful, the current they put out is rising. Inverter manufacturers have been a little slow to adapt their offerings to match these growing PV powerhouses we put on the roof.

So the upshot is that, even though they are acceptably rated under normal conditions, some cheap inverters with lower-rated currents can’t technically be used with the newest high-power PV panels because the AS5033 calculations call for a 1.25 multiplier to address potentially abnormal conditions.

Better inverters will cope easily, but they will struggle to have PV arrays connected in parallel within the rules. When two panels are connected in parallel, the current going into the inverter doubles. Multiply the doubled current by 1.25, and you’ll breach many inverter current limits. If you can’t parallel solar panels, it gives your solar designer less flexibility to deal with challenging roof sizes and multiple orientations.

If you can’t easily parallel panels, you have to keep them all in series. Series panels keep the current the same but increase the voltage with every panel added. This gives a double whammy in that it penalises those trying to build a large system under the other uniquely Australian idiocy, which is a 600 VDC ceiling on non-commercial solar power systems. We thought this particular bugbear was dealt with in the updated solar array standard (5033), but alas, the solar inverter standard (4777) still contains the 600 VDC obstruction. Hooray for harmonised rules.

We can get around this problem by still going parallel, but using fuses in the DC wiring system. However, they are another expense to buy and install, and more importantly, they introduce an unreliable link in the chain. Thermal cycling means they -will- eventually fail.

The current2 state of play seems to be this :

- Inverter makers are putting out declarations that say their product is fine, and you can drive them harder than the sticker rating says. Fronius, Delta, Sungrow, SMA, Goodwe, Fimer (formerly Aurora & ABB) as well as SolarEdge have all submitted documentation. Some are claiming this is not good enough, and the specifications on each inverter must be changed. Sigh.

- The Smart Energy Council is calling it a hot mess. There is no mechanism to allow an official ruling to be made on the issue, but manufacturer declarations are a neat enough solution.

- The Clean Energy Council, our illustrious proactive industry regulatory body have put out a note that I’ll paraphrase simply as this: “¯\_(ツ)_/¯ talk to your state technical authority.”

- The New Zealanders seem to be taking it more seriously than we are, just for a change.

- The guys on the ground are happy to ignore it because the shouting appears to have died down a bit.

- This might rear its ugly head again if the CER decide it’s a problem in their next raft of audits.

It’s not really an electrical problem but a problem of (over?) regulation we’ve all got to deal with in the real world.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

Anthony:

There is a lot of mis-information and mis-interpretation around Solar PV Cell technology and you have picked on the single most unpopular point of contention, which is Isc.

The Standards Committee members responsible for AS 5033:2021, by their own admission, have not done justice to the subject of Isc. Don’t believe me; give well known member Geoff Bragg a call.

Solar PV Cell – Output Power:

The power generated and available for use, from a photovoltaic cell [or module of cells] at any point along the specified IV Curve, is calculated using Ohms Law, and is the product of Current and Voltage at any specific point on the Curve, expressed in watts [P = I x V].

At the Short Circuit Current Point [Isc] the power output [P] is ZERO, since the voltage is zero; whilst at the Open Circuit Voltage Point [Voc] the power output [P] is also ZERO, but in this instance it is because the current is zero.

The history of factor 1.25 goes back a long way and was introduced initially to streamline calculations for system designers regarding the Maximum PV Voltage possible, due to: [1] Array Ambient Operating Temperatures [Maximum and Minimum] at any specific location, and [2] The particular Cell Temperature Coefficients specified by the manufacturer for the PV cell / array under consideration.

It was a generous [and safe uplift] approximation factor to streamline the system design calculations.

Important to note: is that some system designers still prefer to do the long-hand calculations for PV Array V.max rather than applying the arbitrary 1.25 Multiplier Factor. Depending on the array location and historical temperature data available for that location, a significant design advantage may be realised for the calculated number of PV Modules acceptable in a series PV string.

Important to note is: there are other calculations [Fault Current Protection Scenarios in PV Arrays for example] that also use a recommended and arbitrary 1.25 multiplier.

Lawrence Coomber

Thank you Lawrence,

I ran into Geoff Bragg at a recent roadshow and extended him thanks, as I do to you now, for offering expertise and advice.

Most appreciated

Cheers

How do these issues affect the choice of micro inverters versus multiple panels to one inverter?